Personal Column: Iranian.

Me at a protest in Austin, TX against the Iranian election in 2009.

“My parents were born in Iran.” A sentence I say with little weight constantly. I don’t have time to explain what that really means. To explain everything the simple statement keeps hidden.

“Yes, I have an Iranian Passport but, like, I can never really go there because of the regime,” or take care to explain why, “No, I’m not Muslim, my family has never been Muslim, Iran isn’t really a Muslim country actually.”

Despite all this, I feel I should explain because my name is Nicki Anahita and I am Persian or Iranian or whatever I feel like saying that day. My first language is Farsi and I had to learn English in preschool. I was born in Houston, Texas to Tourang and Banafsheh— my parents.

Tourang. He is a thirteen year old boy living in Tehran, Iran with his parents, sister, and two brothers. He is sent to America by himself to get a better education so he’ll go back home and become a lawyer just like his father. He attends a Catholic boarding school in Ojai, California as an atheist. His father, one of only two lawyers with his specialty in Iran, sends money to pay for his schooling.

Banafsheh. She is an 8 year old girl living in Rasht, Iran with her parents. Her mother is a grade school teacher and her father is a well-respected theatre director. She loves science and acting in her father’s plays. She sees her family all the time and loves playing with all her cousins.

For Tourang, the plan to go back home soon slowly shatters as tensions rise in Iran. Suddenly, his father is having trouble getting the money to him because of Iranian conflicts with the US at the time. Calls keep dropping, letters aren’t guaranteed to be delivered, communication is lost. He truly is on his own now. It’s the late 70’s and revolution is occuring back home and he is stuck by himself in California. Getting a law degree in the States would be pointless since the laws in the two countries are vastly different, so he picks the first thing that interests him— computer science.

Banafsheh is young when things start changing, but she notices nonetheless. The writing is on the walls for her family as it’s getting harder and harder for her dad to direct so they move to a new city—Ilam, Iran and her brother is born. Her mom works as a principal of a daycare and her dad teaches at a university. There’s a new regime coming up. The Shah is gone. Iran changes to the Islamic Republic of Iran. Then it begins to outlaw people’s lives. Hair-scarfs are enforced, art is banned—her father’s livelihood is banned. Her parents have to leave, they can’t raise their children in this environment anymore. They immigrate to Vetlanda, Sweden. She is 14 years old.

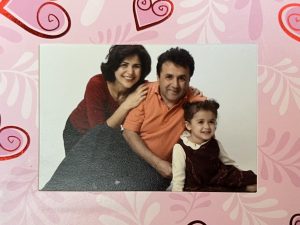

They both grew up enough and met each other via a website he created.

“You are cordially invited to the wedding of Banafsheh and Tourang on July 11, 1998 in Stockholm, Sweden,” read the wedding invitation I found this past summer at my grandparents’ place in Kallhäll. It was in comic sans and bright green. I made fun of them for that.

They moved to the States after the wedding and had me six years later. They named me Nicki Anahita. Nicki meaning “good” or “goodness” in ancient Farsi, and Anahita being the name of the Zorastrian (ancient Persian) goddess of wisdom, fertility, healing, and the waters. I always joke that my parents must have had high expectations for me by naming me “good goddess” but I’m glad they did. I’ve met so many people who despise their names, whether it be their first, middle, or both. They hate them so much they don’t even go by it. I’ve never quite understood that feeling. My names have always brought me a warmth, like a torch strapped to my back my entire life signaling who I am. I was named to be Persian, to be a conduit to the preservation of my culture.

I grew up hearing from my dad about how the regime kept trying to erase Persian history and culture in favor of Islamic culture, how the government tried to stop the Persian people’s celebrations of Sizdah Be-dar and Charshanbe Soori, how they tried to make an incredibly joyous and lively culture somber by removing its celebrations of light and life. His anecdotes are why it’s always made me mad when people assume I’m Muslim, because I’m not. I have no disdain for any Muslim people or Islam in general, but I am not part of that culture and I never will be. It angers me because if not for the heavy hand of the Islamic regime in Iran, people wouldn’t assume I’m something I’m not. I don’t have an Allah (god), and I don’t like that “Allahu Akbar” (God is Great) is on our flag now because, yes, many Iranian people are Muslim, but Persian culture is not Islamic culture.

Once I overheard my mom on a rant to my stepdad. She was angry. She had recently reconnected with one of her childhood best friends from back in Iran who hadn’t left after the revolution. They used to be incredibly close but apparently, she had changed a lot— more than the normal changes that happen as you grow older. According to my mom, she had been “indoctrinated.” Before the revolution, she and her family weren’t religious at all.

My mom was confused because, “She was like the last possible person you would expect to ever find religion! She’s not a fanatic or anything but it’s so odd.”

My dad has always been invested in the social and political issues in Iran. He tells me stories of how he would take me to protests against the regime on the infamous Galleria Smoothie King corner, or bike protests around Rice Village, or even going to Austin protests with the entire extended family all the time when I was five. I don’t particularly remember the exact issue that happened in 2009 but I remember being upset about it.

I don’t remember some of the stories my dad tells me about myself. Like how I came home one day asking if I would have straight hair when I grew up and cried when he said, “No, you’re Persian, curly hair is in your blood.”

But I do remember what led up to that. I remember being three when girls at my school made fun of me for having curly hair. We were sitting on the monkey bars and they laughed at how different it looked. They told me I needed to brush my hair out. I listened and showed up with a puffball of frizzed-out hair on my head the next day. I think that made my differentness worse.

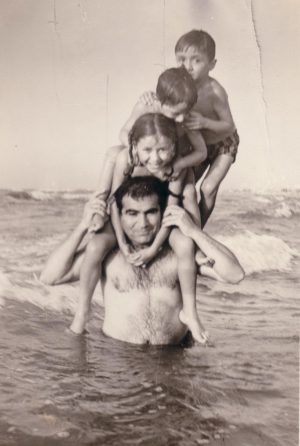

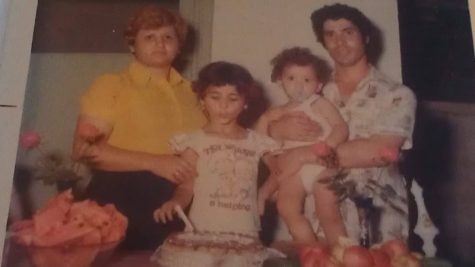

My mom loves to show me pictures of her life back in Iran. Photos of my grandma, Maman Kobi, wearing groovy 60’s and 70’s clothes, just like women in America wore at the time. Photos of my mom at family events and pictures of her childhood home. I’ve always loved seeing how her life used to be and envisioning myself in her place, we look incredibly alike so that was easy. As a child, I dreamed of living in the Iran she described among the snow, and grass, and sea, and mountains. The women would all have long, beautiful hair, cats would roam the streets, a vegetable cart man would go around our neighborhood every week, and I’d always be surrounded by family. I used to have two dolls. I named them Sara and Dara and I was their mother. We lived on a mountain in Iran and I would trek down everyday to get our groceries. I was broken when I realized that the version of Iran I was sold didn’t exist anymore and probably wouldn’t ever again.

I’ve never been to Iran. My grandparents go back sometimes to deal with financial affairs and see their family and friends that are still there, but I’ve never been. I’m not sure if I ever will. I have a friend who goes sometimes. She’s younger than me by two years and she went for a month this past summer. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t jealous. I know why I can’t go. I will never wear a hair-scarf, I will never dress “modestly” in hot weather, I will never not be openly myself, so I will never be able to go to Iran. However, knowing why doesn’t make it hurt any less.

My parents made sure to teach me Farsi as a kid, even taking it so far as to lying to me about not being able to speak English until I was in kindergarten and accidentally overheard my dad on the phone with my school. As a kid, I didn’t understand why they lied but I get it more now. I would have stopped speaking Farsi if they didn’t. I used to be able to read and write in Farsi but I slowly lost that ability over the course of my American schooling because I didn’t want to be different from the other kids so I stopped practicing. Not sticking with it has been an incredible challenge. It’s meant entirely relying on my parents to help me find my own footing in my culture. I constantly have to ask them to read me something or write down what I want to say.

Despite my language barrier, I have a favorite Persian poet— Forough Farrokhzad. I found a translated collection of her poems one summer and fell in love. I know that the English translation isn’t the same— it feels different, has different emotions, but it feels good. It feels good to read the words of an Iranian woman in love without any censorship or constraint. She died early, over a decade before the revolution so the version of Iran she lived in was akin to the one my parents had described to me. She was a revolutionary in her own right, writing about her affairs and lovers mere years before it was banned for women to be seen in public with a man she wasn’t married or directly blood related to. She felt freely and I connected with that. Most modern Persian art is tainted by a fear of the regime and being imprisoned or killed over producing the wrong thing and to see a contemporary artist not feel the looming hand of the regime gave me hope that we could still achieve that because if Iran was able to change so quickly, within the span of my parents’ lives, maybe it could change back during mine.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Carnegie Vanguard High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs and fund field trips, competition fees, and equipment. We appreciate your support!

Current senior Nicki is a writer for the Upstream who also manages the site. She loves Micheal Cera and has never not cried while watching Mamma Mia! and...

Sarah Mirnik • Dec 14, 2022 at 12:27 pm

So beautiful! It brought tears to my eyes and took me back to about 40 years ago.

Mahsa • Dec 14, 2022 at 9:19 am

Guys I’m the friend!!!!!!!!!!!!

Ava Manchac • Dec 13, 2022 at 10:31 am

man i love this so much. especially the line “I was named to be Persian.” This is so good.