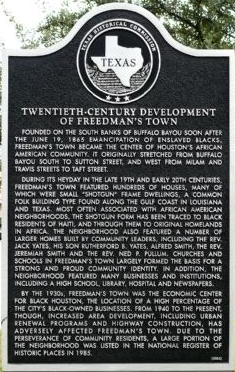

After a long and busy day at Carnegie, the bell finally rings, and almost 900 students bustle off to hang out in the neighborhood. They can choose from a variety of places, such as the Barnaby’s Cafe or Pink’s Pizza, but this modern scene contrasts the area’s extensive historical roots. Just outside West Gray St. lies a sign that says “Historic Freedmen’s Town District.” Courtesy of the Harris County Historical Commission, this marker indicates that Carnegie is in the Freedmen’s Town area, a deeply historically significant piece of Houston.

Freedman’s town (part of the Fourth Ward area), dates its origins back to the mid 1800s, when in 1865, the Union Army arrived on the shores of Galveston, Texas, announcing the federal order granting the freedom of all 250,000 Texan enslaved people. Countless newly freed enslaved people settled near the Bayou, the cheap land giving them opportunity to build a new life. They organized their own school systems and churches, even paving the roads by hand. This community blossomed into Freedman’s Town, the first independent African American neighborhood of Houston. The rapid development of businesses, churches, and nightlife, developed Freedman’s Town and its surrounding communities into the larger Fourth Ward. However, through land development and a growing urban landscape, only 50 out of 568 original Freedmen’s Town structures still stand today, as well as countless residents being displaced, and newer businesses encroaching on the area. This displacement of Black residents and loss of important historical landmarks in the name of urban development and new architecture is one of Houston’s earliest examples of gentrification.

To offer some more insight, Mister McKinney, a Houston historian and creator of the Houston History Bus (a Houston bus tour designed as an educational tool for all ages interested in Houston’s history) expanded on how exactly Houston lost so much historical property.

“Houston is one of the only major cities with no zoning. We don’t require specific land use in certain areas. So for that reason, we have been known to tear down a lot of our historic structures over Houston’s history.” Mister McKinney said.

A notable development highlighted by McKinney was the construction of Interstate 45, an installment that displaced some 40,000 Freedmen’s Town residents. He explained how the freeway coming in the late 50s defined the boundaries for modern day freedmen’s town by bisecting the rights of the African American community.

“Freedmen’s Town used to be very large, it went all the way over to Allen Center, which is around Smith Street and Louisiana street. And the freeway comes in and takes a majority up and then, kind of, cuts everything off.” McKinney added.

Moreover, he shared a broader perspective on this urban development, stating that it’s common for many American cities to put a freeway through minority communities, because they are less likely to voice their concerns and derail a freeway project, and lack the resources to do so versus a well-educated white community.

He also discussed the impact of rising property prices on the community, “Where they could have originally been able to afford to pay rent on a one bedroom, and a shotgun house. With the rent of 300 bucks to 500 bucks a month, now they’re having to pay 1500 bucks a month, three times that amount, that not everybody can afford, especially the original people that lived in the neighborhood. And that’s an example of gentrification by pushing people out that were there first, by increasing prices.” McKinney said.

McKinney also emphasized the need to strike a balance between progress and preservation in Houston’s neighborhoods: the balance between preserving valuable buildings while also allowing a community to grow and expand. He stressed the importance of citizens and communities honoring and being respectful of the past.

When talking about the importance of learning about Fourth Ward/ Freedmen’s Town’s history, Mister McKinney added, “What it does for us is it paints a picture of a diverse community that is still there, because there are still people that are very connected to that community since their families have lived there forever. So, it’s a chance for us to learn about the history of who used to live there, and then study that”

In terms of ongoing efforts to preserve Fourth Ward’s history, McKinney highlighted the efforts of some organizations such as The African American Library-Gregory school who educate through monthly educational programs on African American history in Texas and Houston. As well as the The Freedmen’s Town Conservancy Non-Profit, an organization dedicated to Freedmen’s town education and conservancy that helped the area become a UNESCO (The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) World Heritage Site.

McKinney’s own organization, founded in 2002 Mister Mckinney’s Historic Houston, also does important work in educating Houstonians on the history of not only Fourth Ward and Freedmen’s Town, but all of Houston’s extensive history. They do this through things like their educational bus tours, which essentially serves as a mobile classroom to anyone interested in Houston’s history.

As students step out of the halls of Carnegie and into the surrounding neighborhood, it’s crucial to recognize the historical significance of the area. The lessons of Houston’s history, like those of Fourth Ward and Freedmen’s Town, provide valuable insights into the past and shape understandings of the present. The issue of gentrification is ongoing throughout the U.S., which erodes the cultural fabrics of communities. Preserving history and cultures is essential because it allows residents to understand and appreciate the diverse stories that have shaped the communities. The ‘Historic Freedmen’s Town District’ sign hopefully serves as a tangible reminder of the valuable legacy that resides within Carnegie’s community.