When MiHoYo released Genshin Impact in 2020 across many platforms, they doubtless expected a grand opening. It’s possible, however, that they didn’t expect it to become the largest international launch of a Chinese game ever. This viral game has a large, dedicated fanbase, and makes Hoyoverse a lot of money: $1.9 billion in 2022. Genshin Impact, along with Hoyoverse’s other well-known offerings, Honkai Impact 3rd and Honkai Star Rail, has become one of the most iconic gacha games in a gaming landscape increasingly beset by microtransactions and addiction-encouraging design.

Gacha and lootbox-monetized games are so similar that they might as well be the same thing, according to the Minnesota Journal of International Law. Games that integrate gacha and lootbox mechanics have in-game, virtual currency, usually acquirable both through in-game activities and, much more easily and conveniently, for purchase with real-world money. This in-game currency is used in set amounts to purchase randomized in-game units, anything from cosmetics to items to characters. The player buys a thing in the game, and whatever that thing is will be revealed to them once they’ve paid for it. Usually, desirable units (whether truly useful, like a powerful character, or just wanted for their own sake, like an event-exclusive cosmetic) are made rarer and more difficult to get, to encourage players to spend more. The player is rolling the figurative dice that the unit they receive is going to be the one they want; thus, many game players refer to their interaction with the mechanic as “rolling” for whatever unit they’re hoping to get. According to a survey for which a QR code was posted around the school, 25% of Carnegie students play at least one gacha game.

They’ve become increasingly popular around the world since the first recorded mobile gacha game (as we would recognize it now), Konami’s 2010 Dragon Collection. There are a few subtle differences between lootbox and gacha. Lootbox mechanics usually contain multiple gameplay units (characters, items, cosmetics, or otherwise) and are often recognized integrated as a feature into games that a player has to buy first, as in 2017’s Middle-Earth: Shadow of War, while gacha mechanics are usually one gameplay unit per “roll” (unless, of course, you’re pulling for many units at once), tend to appear in free-to-play games (which often have some sort of stamina mechanic that limits playtime per session), and are more vital to gameplay, like acquiring characters to use, to the point that tutorial levels might include the player’s first gacha roll of the game, as in Twisted Wonderland. If that all sounds an awful lot like gambling, you’re not far off.

The difference according to UK law, at least, is that when somebody gambles in a casino or on the lottery, the money they win is useful outside of it, whereas in gacha and loot boxes, the prizes aren’t useful outside the game. This is a distinction made even more arbitrary by the fact that many websites let people exchange such in-game prizes for real money.

Japan banned complete gacha, a model in which players must collect several randomly generated prizes to get the final prize, in 2012 after several highly publicized instances of children spending big on games. Belgium banned loot boxes in games in 2017, shortly after the controversy surrounding the release of EA’s Star Wars: Battlefront II, which drew ire from gamers when important characters and objects that provided gameplay advantages were made very difficult to acquire without large amounts of in-game credits; gamers felt the game was pushing a pay-to-win model.

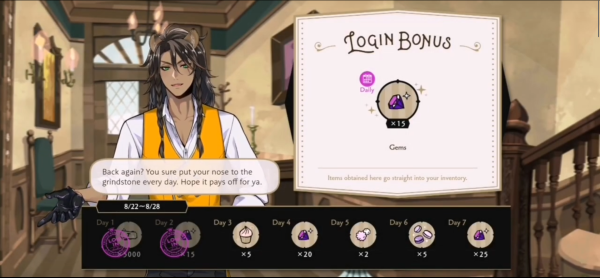

China, however, has some of the strictest rules concerning video games, which state media has allegedly called “spiritual pollution”. They set strict playtime limits for gamers under 18 in 2021, enforced by games and social media apps through features like “youth modes”. Chinese law also requires that rates be published in official game materials, like on the official website, in addition to giving players some high-level reward after a certain number of pulls, a system known as “pity”. In new regulations announced last December, China banned daily login rewards, rewards for spending consecutively, and rewards for spending on the game for the first time. Stocks in large game companies like Tencent dropped in the two-digits. But, of course, these rules only apply in China. Games produced in other countries, like Disney of Japan’s Twisted Wonderland, my personal indulgence, can offer these incentives as much as ever, and the version of Genshin Impact published by Hoyoverse, the international publishing arm of the Shanghai-based MiHoYo, doesn’t “seem affected”, at least on the North American server, according to a student who plays Genshin but declined to be named for this article.

US circuit courts are still split on whether gacha and lootboxes constitute gambling. Judges are uncertain on how to judge the value of virtual, usually in-game, currencies, and our laws concerning gambling don’t easily accommodate electronic gambling like gacha and lootboxes. At Carnegie, 20% of poll respondents play gacha games of some sort, and those who gave their opinion of gacha games do not like them, saying they’re “unfair”, “ridiculous”, and “contribute to worse games”. Carnegie also seems to be blissfully free of the spending problems that plague many college campuses, where sports betting addiction is on the rise. This may be because many Carnegie students, especially seniors, have a good deal of independence in daily life; a study on loot boxes in FIFA Ultimate Team found that a need to experience autonomy was the strongest motivation for spending behavior.

Game development studios need money, obviously, but it seems that microtransactions are an especially underhanded way to earn it. Tribeflame CEO Torulf Jernström put it quite plainly in his 2016 talk Let’s Go Whaling, given at Pocket Gamer Connects Helsinki, where he, after saying he’d “leave the morality of it out of the talk”, outlined, among other tactics, a strategy called “Hook, Habit, Hobby” to entice players to spend and keep spending. He stated that one of the most important parts of getting a player to start playing is to “break the ice” and convince them to spend for the first time, and in addition detailed a need to bypass players’ “slow brain” to get them to impulse spend.

Gambling addiction is not mere financial irresponsibility; it ruins lives, and the business model of gacha and lootbox-monetized games actively preys on and encourages such addictions. One chilling anecdote of a drug addict who attempted to replace drugs with video games as a healthier alternative, and then found themself chased from game to game, displays the way this takes advantage of vulnerable people. These “whales”, a small proportion of players who spend large amounts, tend to make up most of a given game’s revenue with their spending; most players of mobile games, as well as most surveyed Carnegie students (85.7%), have never spent money in a mobile game. This is what game developers seem to consider an unfortunate reality. Encouraging spending is one of the functions of using in-game currency; the often complex currencies used in gacha games create a mental separation between the in-game currency and actual hard cash, not unlike casino chips.

This all makes it no wonder that gacha games are often accused of being predatory, but it’s not the only reason. Many games are made to be addictive, with flashy graphics and enjoyable gameplay loops, but gacha has many additional strategies. Gacha games often have limited-time “banners” for in-game units to play on the fear of missing out, or FOMO. Perceiving that something is only available for a short time can stop you from thinking about whether you really want the thing, only that you have to get it before it’s gone. The social side of FOMO is also encouraged by another of the strategies Jernström outlines: to cultivate a culture of spending in-game to encourage players to see spending as “normal”. This can be encouraged, even without the efforts of game developers, by jokes between gacha gamers about, for instance, how empty their wallets are, and by the very nature of competitive multiplayer games like Star Wars: Battlefront II or the Call of Duty games; spend money to upgrade your gear and retain your status. Of course, players are often rolling not just for the pleasure of gambling but for whatever specific thing they want; many gacha games have a variety of characters that hook players, and it’s an acknowledged phenomenon in fan spaces that people will start playing for one character and stay for another, or stock up on in-game currency for their favorite character; “I need to save, no way I’ll miss my king!” one Reddit comment says of a card to be offered in a believed-to-be-upcoming event for the English version of Twisted Wonderland (the same event already happened in the Japanese version). That’s another strategy: lack of transparency, and not letting players know far in advance what’s coming. If players are kept on their toes until, for instance, a week before an event or banner, FOMO is in full force, and it becomes difficult to save up in-game currency, which encourages spending.

A common argument in favor of loot boxes boils down to a claim that the sale prices or budgets for AAA games just aren’t enough to pay for licenses for the FIFA games, for instance, or to provide a living for the hardworking programmers, artists, and other game development staff. This isn’t true, at least not for AAA games featuring lootboxes; AAA games are made by large studios with a lot of money to throw around and usually cost quite a bit at release. And this extra money isn’t necessarily actually good for player experience, even when it entirely funds free-to-play games like the Honkai games; surveyed Carnegie students thought gacha mechanics were “unfair”, “annoying”, “unnecessary”, and “contribute to worse games”. Games developers interviewed by Lies van Roessel claimed that a driving aim of their game design was fairness, but it seems it is the rare gacha game that feels possible to successfully progress through for free-to-play players, and even more rare that free-to-play and paying players should feel that they experience the same levels of difficulty progressing.

The democratic lawmaking process is slow, especially in our current polarized climate, but the US needs more stringent laws to limit the ability of game studios to take advantage of players who are susceptible to these tactics-which is, really, everybody, because these tactics are built on behavioral psychology. We experience more satisfaction upon getting variable rewards than if the reward is dependable; that’s part of why gambling in all its forms is so popular. But the especially vulnerable, gambling addicts and children, and everyone whom these tactics and the studios who use them seek to take advantage of deserves better than to be left to the whims of corporations that only seek to make themselves a profit. We need to update our laws to account for electronic forms of gambling, we need to stop stigmatizing addiction, and we need support for addicts of all stripes, especially those whose addictions and genuine problems are dismissed as “irresponsibility”.

Kara • Mar 4, 2025 at 10:31 am

gacha life is cool