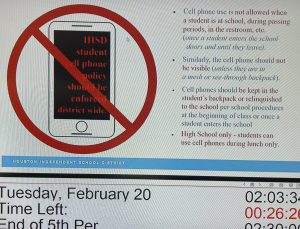

On Tuesday, Feb. 6, Carnegie began enforcing a cell phone policy banning cell phone usage on school campuses for all students across the Houston Independent School District (HISD). This policy was officially enacted by HISD on Aug. 28, 2023, but it had only started being implemented due to the Texas Education Agency’s (TEA) takeover of the district. This came as a surprise to most students, who were informed of this change by the newly added slide on the TVs in classrooms and hallways across campus.

High school teachers and staff must now confiscate phones if the phone is at all visible on school campuses at any time other than lunch. This includes the time before school, during class, in the hallways during passing periods, as well as in school bathrooms. According to HISD, the policy’s rationale is that “use of phones during the academic day disrupts learning and instruction, fuels disputes between students, and undermines the culture [they] are working to create in all HISD campuses.”

To the best of our knowledge, this policy has since been implemented and enforced in all schools across HISD, an action that has led to mixed student opinions, but general success in reducing phone usage.

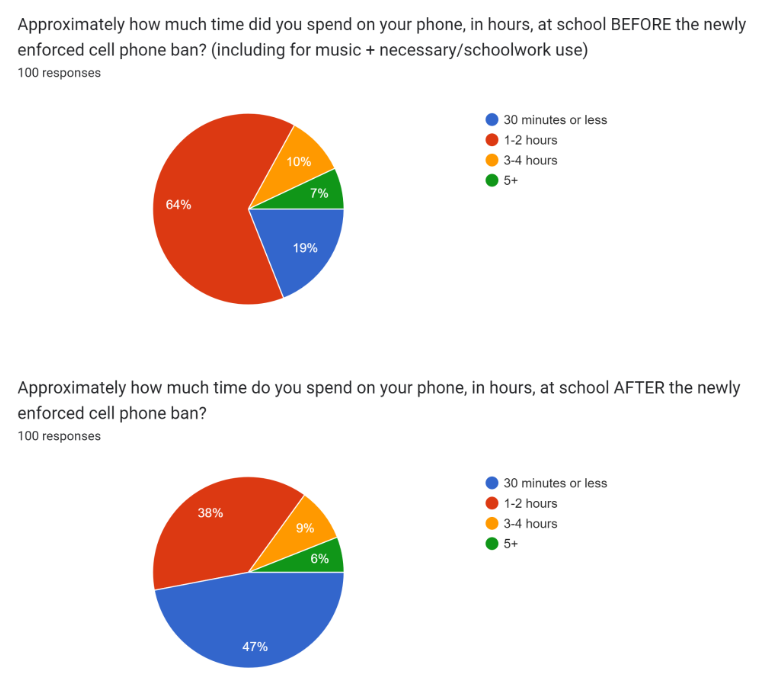

According to an anonymous survey conducted by Upstream News on 100 highschoolers across HISD, the percentage of students reporting less than 30 minutes of time spent on their phone increased from 19 percent to 47 percent after policy implementation, while the percentage of students spending more than 1 hour on their phone dropped from 81 percent to 53 percent.

In addition to the observable effects, student opinions are skewed in regard to overall approval of the cell phone ban. 85 percent of the students that were surveyed either strongly disagreed or disagreed that the cell phone ban positively impacted their school experience.

“The use of my phone at school has no effect on my academic tendencies, and banning them causes more issues than anything positive. If people aren’t on their phones, they’re distracted by something else,” an anonymous survey respondent said. “The phone isn’t the problem, and it’s sad that HISD officials are focused more on banning them over making policies that actually help their students.”

The majority (64 percent) of student survey respondents strongly disagreed or disagreed that cell phones were a distraction to learning.

“I think it’s really important that we not only look at the cell phone as restrictive but instead it can be a great way for students to engage with their material in new ways, in diverse ways. And I think that rather than reject technology, we should incorporate it more in classrooms,” said Junior Hira Malik, president of the Community Voices for Public Education Club.

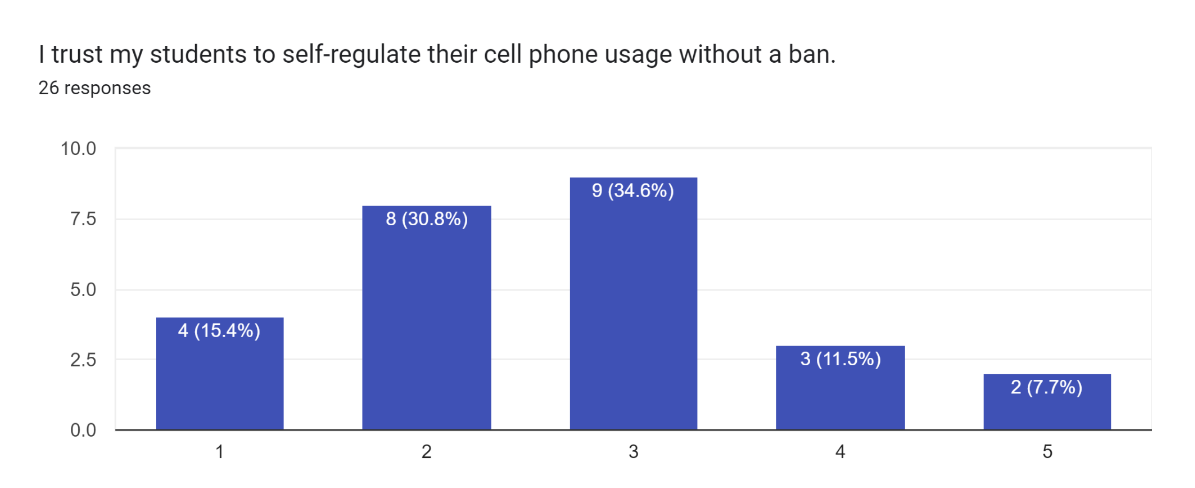

Teachers agree, somewhat. A survey conducted on 26 Carnegie teachers showed that over half strongly agreed or agreed that cell phones could be used in ways beneficial for student learning. However, views on phone regulation seem to be more divided. When asked to indicate their agreement with the phrase, “I trust my students to self-regulate their cell phone usage without a ban,” most respondents expressed neutrality (35 percent) or disagreement (46 percent).

Despite teachers generally being more against phone usage than students, concerns similar to those of students have arisen regarding HISD’s particular approach to the issue of cell phones.

“A lot of students have developed a real dependence on [phones]. And I think that’s problematic. I don’t allow kids to hang out on cell phones like I want us to be present together,” AP Human Geography and AP Government teacher Charlotte Haney said. “[But] this policy is being kind of in a draconian way implemented, and it seems very arbitrary.”

The policy only allows confiscation of cell phones if the phone is visible to teachers and staff, implying that phones that are not visible to teachers and administration are still in the possession of students.

“I think thus far, and hopefully it stays this way, the campus is not confiscating cell phones, so students will still have them on their person. So while you’re not allowed to be using it, if there really were an emergency, and the student really needed to be reached by family or reach out to their family, they would still have it on their person,” Kris Casperson, AP Literature teacher, said.

Students voice apprehensions about the possible lack of communication, a response driven especially by recent school shootings, an ongoing trend across the US, and other emergencies. Madison High School’s walkout, for instance, was driven by the administration requiring students to turn in their phones before entering school, making the school’s staff the only means of communicating with their families for the entire student body.

“We can go all the way to the extreme with things like school shooters and not having the ability to contact your parents or authorities or whatever. If there’s an emergency in your family, and you [don’t] have access to your phone,” said Devan Chadha, CVHS Student Council Treasurer.

Survey results indicate that the majority of students feel the same way. 54 percent of respondents identified communication as the main purpose for using their phones while at school.

“I think that it really is a public health and safety concern,” said Malik. “When we look at school shootings, I think it really disconnects students from their families. We don’t know what is happening to our family or our friends or anybody when we can’t access our phone.”

Unlike the majority of student responses, which generally indicate anti-ban perspectives, teachers’ views on phone regulation appear to be more divided. When asked to indicate their agreement with the phrase, “I trust my students to self-regulate their cell phone usage without a ban,” the largest share of respondents expressed neutrality.

“To just unilaterally take a privilege away and act like there are no scenarios where it’s beneficial, I think that could have a ripple effect that we don’t want to see in our district, which is students really feeling overlooked,” Casperson said.