Cannonballs rip through the air. The formidable enemy stands just 100 feet away, thinly veiled by the shrubbery dotting the hilly battlefield. The World Wars class is now officially waging war against the freshmen — a spur-of-the-moment decision in the reenactment of historical battle formations.

Fast-forward a few decades in history to the height of the Cold War. Shrouded in paranoia, the 1968 class must hunt down the communist infiltrators. But in this round, everyone is secretly a communist.

It’s these activities that make the 1968 and World Wars classes a constant topic of conversation among students. Taught by Nathan Wendt, who also teaches AP U.S. History, the two electives are offered in the fall and spring semesters, respectively.

“In terms of [the] timeline, it would make more sense to put World Wars first. But since they’re two, kind of different classes, [the order] really doesn’t matter, because they don’t really cover the same things,” Wendt said.

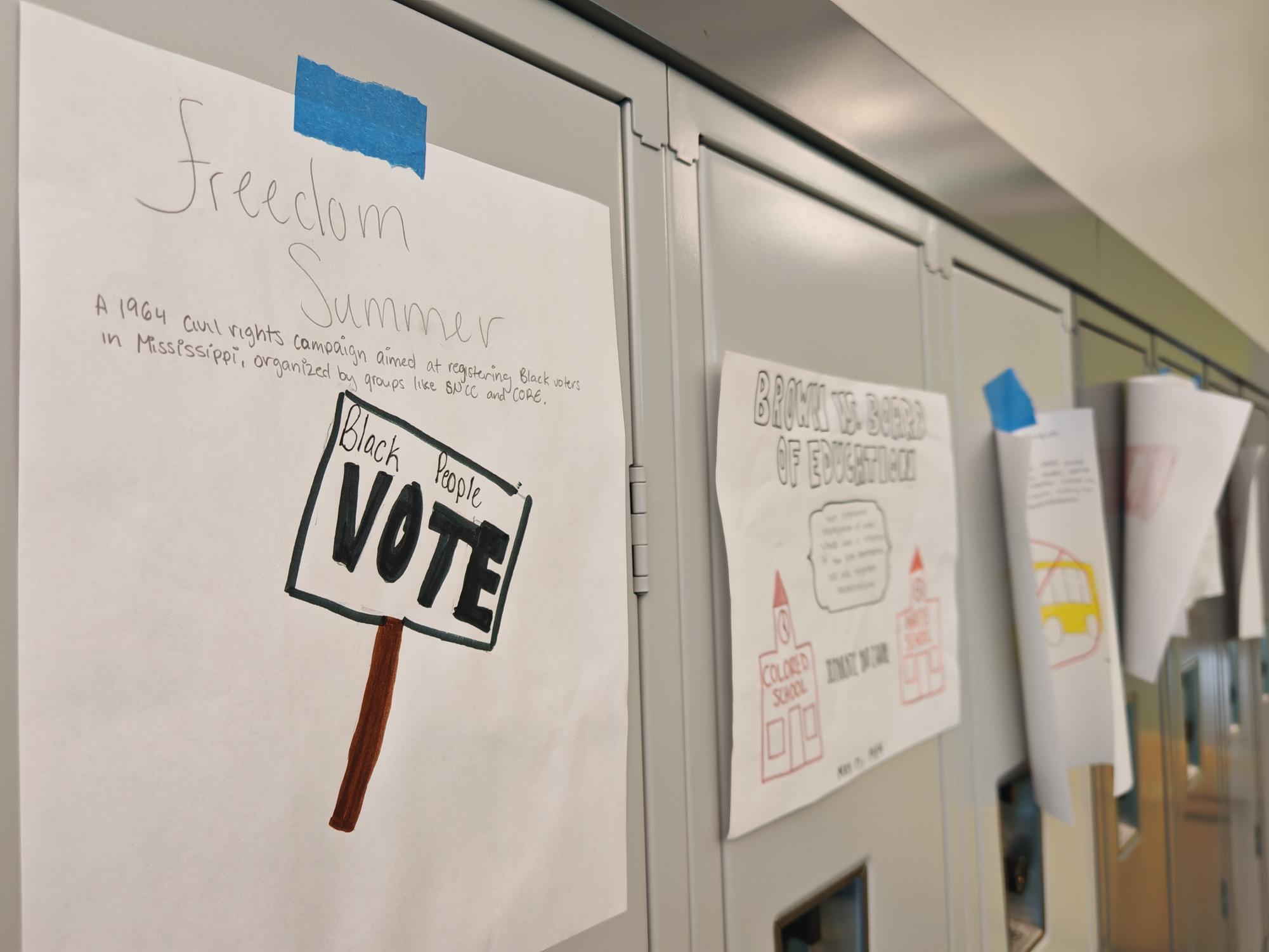

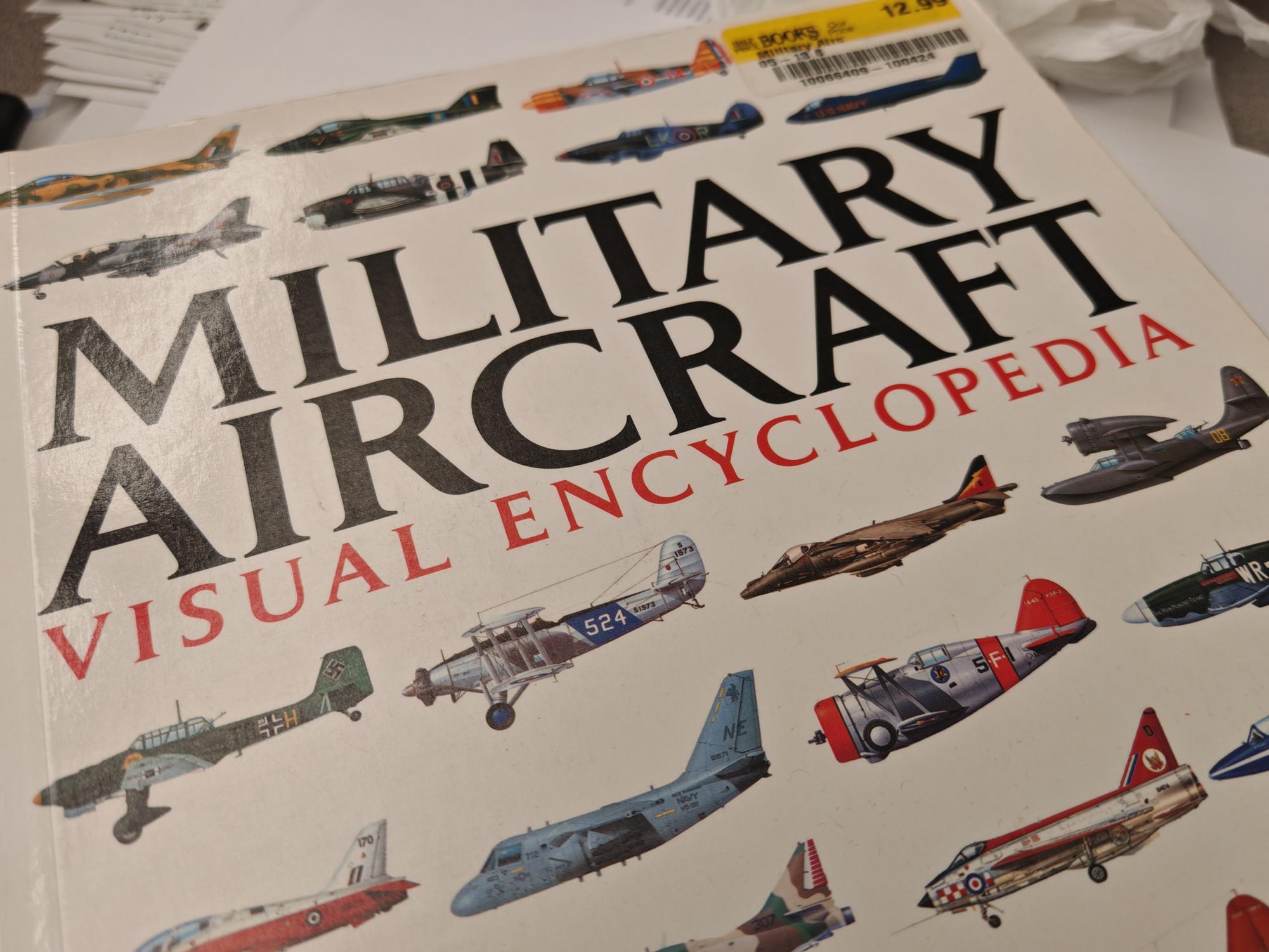

Wendt describes World Wars as a “military history class” about European conflicts from Napoleon to World War II, focusing on how shifting borders and geopolitics can affect other topics like culture and imperialism — and especially foreign policy. 1968, however, is more of a “social history class” covering 1960s-era topics that shaped the life of “an average everyday baby boomer” in the U.S.

“We use 1968 as kind of a focal point,” Wendt said. “However … we can’t just talk about that specific year in general. We have to bounce back [to] where these movements or people or ideas came from, and how they even extend past that year.”

Despite covering some of the same events and ideas as the AP history courses offered at CVHS, the elective courses spend significantly more time with those topics at a greater depth. A survey class like AP World History may spend only a few class periods on World War II before moving on.

“A lot of kids were kind of shocked to learn that [D-Day] was not the first time [U.S. troops] landed in Europe,” Wendt said.

Though Wendt currently teaches the two electives, the courses were originally the brainchild of Andy Dewey, a former CVHS teacher.

“I believe he wrote [1968] in the late ’90s, as that generation of people [the later baby boomers] were starting to become more significant in popular culture, thus driving student questions,” Wendt said. “So that class was constructed basically like his life.”

Meanwhile, the idea for World Wars came from Dewey’s interest in military history.

“He could tell you everything about everything, like how many teeth were on a comb of this one obscure lieutenant’s personal hygiene kit,” Wendt said.

Wendt initially picked up the electives to help the school meet student demand, co-teaching with Dewey for his first year to get the feel for the class.

“I understood that it was important to Carnegie — to the students that have those interests — to have an avenue in which they could learn more about those topics. And so that’s why I was cool with picking [the electives] up,” Wendt said.

Though it didn’t come without its challenges.

“Some of [the 1968 lesson plans] were literally ‘describe my life in the ’50s,’” Wendt said. “Versus World Wars, which was kind of on the opposite end of the spectrum.”

With time and experience, Wendt eventually struck the right balance of speed and detail. By combining his content knowledge with his own strong suits, Wendt found his footing with the electives.

His teaching style keeps in mind the workload his students already have. Though the two classes cover content in greater detail than the AP history courses, Wendt tries to avoid assigning nightly textbook passages and reading notes.

“It’s an elective class. People who enjoy history choose to be there, and as a result of that, I’m trying not to bog them down with all this work to make it as rigorous as possible,” Wendt said.

But as district standards change, so must the classes. With the push to include elements like multiple response strategies in lessons, Wendt has had to find ways to incorporate more activities into the electives, which were primarily lecture-based.

“It’s really been tough trying to find good resources to do that with, because this is a unique class,” Wendt said. “This doesn’t follow any kind of state curriculum. It doesn’t follow anything from College Board.”

Over time, however, a list of homegrown activities has taken shape. The hunt for communists — a murder-mystery-esque fan-favorite activity — allows students to work with primary sources from the age of McCarthyism. Tracing maps over time showed the tangible impacts of conflict over decades.

But of all the activities, making the World Wars class march in military formation is probably the most memorable one to Wendt. And it all started with a video about Napoleonic tactics.

“I was watching this short YouTube clip with the kids and kind of talking about various [military] formations. And I’m like, ‘We could do that here. We have enough people, we can try that. Let’s try that,’” Wendt said.

The goal was to demonstrate how military technology and its evolution over time affected the formations that armies marched in battle. The class explored a variety of ideas: inaccurate muzzle-loading rifles from centuries ago, ranged cannons and artillery, modern machine guns, and even pillboxes from World War I.

“We simulated World War I and quickly found out that it’s not a great idea to do that,” Wendt joked.

The activity included other aspects of war, like how different terrains or the inclusion of cavalry can massively impact the course of battle, from preplanning to aftermath. Some freshmen from other classes even joined the reenactments as the enemy forces — albeit after being ambushed.

“They’d flee, or sometimes they’d try to return fire,” Wendt said. “They were good sports with it. We wouldn’t make a big deal about it.”

Between the barked movement orders and the synchronized marches in formation, the activity also served as a way for students to feel firsthand what war was like for soldiers.

“Somebody gets hit in the leg, what do you do then? Do you try to get them out immediately? Do you just press for it? Those are kind of like [the] quick decision-making things that we have to do,” Wendt said.

In World Wars, he tries to emphasize this “real human aspect” of war, even though war is sometimes portrayed as a “glorious endeavor.” And as for 1968:

“One thing that I really want to impart [to] those kids is that [1968] was not again some hundreds-of-years-ago, doesn’t-matter-to-us-anymore [history],” Wendt said. “Because the children who grew up in that time period — that was their reality.”