Less than a mile away from Carnegie Vanguard High School lies the African American Research Center, a vital part of the Houston Public Library system, though perhaps unknown to many students. Walking in, one is met with soaring glass windows, a cozy library where groups are gathered around in conversation and the greeting of a warm smile from the reception desk.

Located deeper within the building is the workspace of the archival team, including lead archivist Sheena Wilson. A history-lover and firm believer in accessibility, Wilson began her employment at the African American Research Center during her years as a graduate student.

“I was in graduate school at Texas Southern University working towards a master’s in history, and studying sources … planning research projects. But I kept running into issues trying to access collections at archives. I thought, ‘How am I going to write the stories I want to write as a historian if I can’t even get access?’” Wilson said.

That’s when she decided to make the shift to pursuing archival work. After debating whether to leave the South, she took an interest in the Houston area, specifically the African American Research Center, which was founded in 2009 by Lee P Brown. Brown wanted the African American Research center to maintain a philosophy of cultivating scholarly work as well as opening up historical records for public viewing.

Wilson has been a part of the African American Research Center for nearly half of the 15 years since its founding. Her day-to-day work consists of engaging with members of a large team, curating specific items and helping to preserve local history.

“We want to make sure we’re handling things with care. We want to make sure that we’re only having to touch each item one time, so we’re going through, we’re processing it, we’re digitizing it, and then we put it up to be preserved, and we don’t have to touch it until maybe a researcher wants to come look at it,” Wilson said.

To Wilson, archiving can create an impact on not only the community, but also herself.

“Archiving is very heavy. It’s very emotional because when people bring in [items] and they’re sharing their stories with you, it always kind of brings you back to a personal moment you have,” she stated.

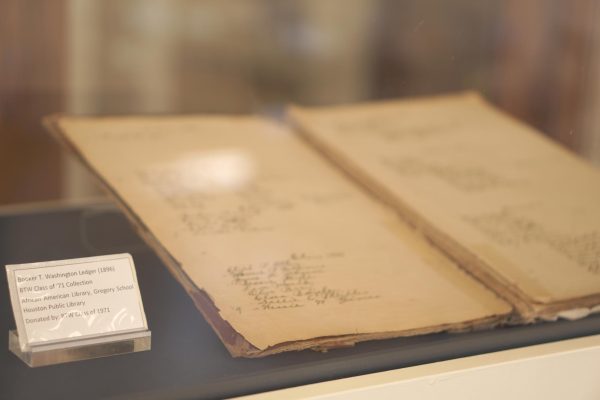

When describing the various objects she has received over the years, Wilson recalls one of the more notable ones — a ledger from Booker T. Washington High School (previously Colored High) that documents the graduating seniors from every class from 1897 to the 1960s.

“Oftentimes we hear that Black people didn’t go to college back then. But this ledger doesn’t just tell who graduated [from high school], it tells what university they went on to. So it’s an interesting little piece of history to kind of go against what everybody else is saying. But hey, we have this real factual document here that is saying otherwise!” she exclaimed.

Juan Garner, the AP African American Studies teacher at CVHS, maintains a similar reflective attitude when it comes to the objective of what is being taught in his class.

“At the root of the class is enlightenment, making people more aware of the African American experience. That is a unique experience, so at the forefront [is] to make people better understand the current situation of African Americans in this particular space of America,” he said.

Wilson acknowledges that history taught in the traditional schooling system is often one-sided — so she emphasizes the importance of evaluating different sides of history, a practice that is best represented through archival work.

“It’s important to have both sides of the story … A lot of times, we’re taught from the top down. We’re taught the politician’s story, we’re taught the leader’s story, but who were these people fighting for? What community were they representing?” she explained.

Garner holds a similar viewpoint, explaining that due to CVHS’ historic location in Freedman’s town, students should be more aware of the history of their surrounding environment. He compares the civilians of ancient Rome who went about their daily lives among grand structures such as the Colosseum to the students at CVHS.

“This town was a center of Black Texas, with over 400 Black businesses right in this little area here. It was a vibrant and pretty much self-sustaining community … Making us aware of that and appreciating where we are is important to me,” he notes.

To Wilson, archival work is a supplement to the impact educators such as Garner can have in classroom spaces.

“Archiving expands on what is allowed to be taught in school. It’s that alternative route of education because in some ways, we don’t have any limits on how we can present information to the public … We can say, ‘Hey, you know what? I think you should look at this collection of papers, because it’s going to complement the area that you’re looking into,’” Wilson said.