Recent survey reveals teachers lag behind student desire to identify gender pronouns

22% of CVHS students reported using non-traditional pronouns in a recent survey.

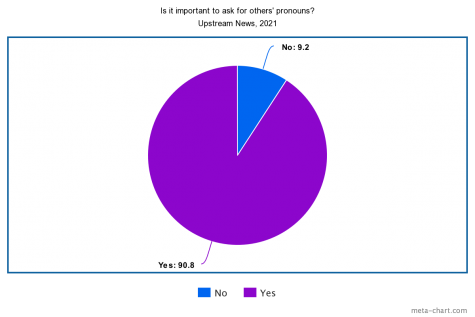

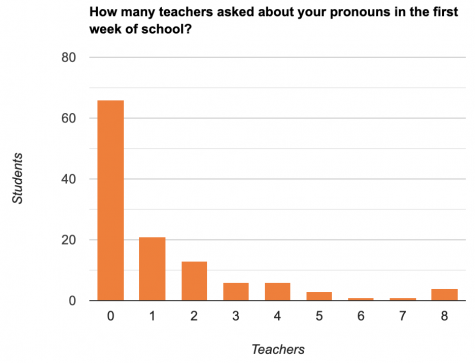

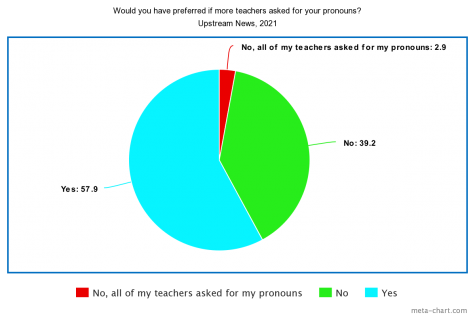

In an Upstream News survey with 120 participating CVHS students, 90.8% of students believed it to be important to ask for others’ pronouns and 22% of students reported using non-traditional pronouns–but only 3.3% of students reported all of their teachers inquiring about their pronouns in the first week of school.

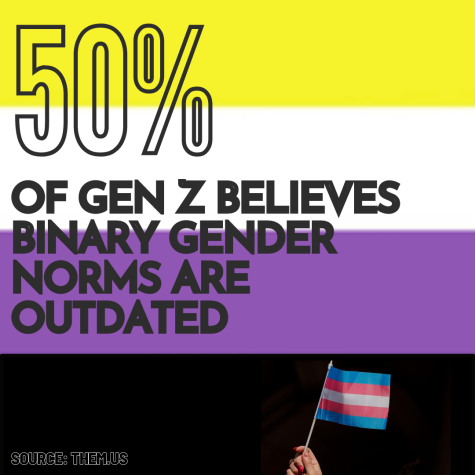

Despite criticism from some, they/them pronouns have gained prominence in use as singular pronouns in the English language. Additionally, 50% of Generation Z (those born between 1995-2010) agree that traditional gender roles and binary gender labels are outdated.

Despite criticism from some, they/them pronouns have gained prominence in use as singular pronouns in the English language. Additionally, 50% of Generation Z (those born between 1995-2010) agree that traditional gender roles and binary gender labels are outdated.

Someone’s pronouns offer self-expressive freedom, according to junior Kent Mascheck.

“I really never fit in as a boy or a girl, or anywhere within the gender binary. So I felt like every time I was out, I’d have to put on a mask,” Mascheck said. “Then I found freedom through my they/them pronouns.”

Duke University’s Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies and the Duke Center for Instructional Technology believe the best way to support this facet of student expression is for teachers to acknowledge it. The institution has training dating back to 2017 recommending all professors to ask for student pronouns.

“Even if all of your students appear to be gender-normative, there may be students whose pronoun preferences don’t match their gender presentation,” wrote postdoctoral associate in Transgender Studies Nick Clarkson at the time of the initial recommendations.

Guidance counselor Marcello Frau also considers asking for pronouns to be essential for student comfort in school.

“You have to ask,” Frau said. “Okay, so you want to go by this name; what pronouns do you want to be identified by?”

However, there can be controversy associated with the issue. Some students, like Mascheck, prefer taking the opportunity of a teacher asking about pronouns to make a “public announcement” of their pronouns to the class. Other students find an interaction in front of the class to be daunting.

“[Asking for pronouns] can make students feel awkward; especially those who identify differently because they may not want to announce it to the whole class,” said one student who participated in the anonymous survey.

This controversy was particularly apparent in the survey, where some students were leery of teachers asking about pronouns in class.

Teacher Samantha Shields offers a solution to this debate.

“I did a survey,” Shields said. “I always ask [for] their name choices.”

But the recent shifts in students using non-conventional pronouns prompted her to add a few questions, including preferred name, pronouns, and where those pronouns could be used.

“A lot of times students will tell me their pronouns, but I’m not supposed to use those pronouns for other people so I wanted to be sure what I was supposed to do because it’s not my intention to make anybody feel uncomfortable,” Shields said.

Without options like Shields’ survey, students can find the process of repeatedly coming out to new teachers intimidating.

“I had to come out to every teacher,” said Mascheck, “and even that’s very confrontational and that was something that’s such like a brand new subject. It’s very scary.”

But Frau expressed that not all solutions need to be as comprehensive. He recommends something “as simple as on an index card.”

However, despite the many different approaches to this issue, there is one clear consensus among CVHS students surveyed: the way schools support gender expression needs to be left up to the students.

Teacher Kristen Davis-Owen puts the heart of educators succinctly. “What I hope schools do,” Davis-Owen said, “is prioritize the individuals in the building above the politics in the building.” Why? “Because they’re the ones who matter more.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Carnegie Vanguard High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs and fund field trips, competition fees, and equipment. We appreciate your support!

Ava Lim is a senior at CVHS. She's a lover of all things neat and pretty, and has a variety of hobbies, ranging from calligraphy to crochet. They love...

Hi! My name is Brooke J Ferrell. I'm a senior who, if not writing, is usually rock climbing :)

Caitlin Liman • Sep 27, 2021 at 8:10 am

As someone who never realized the importance of this for individuals, this comprehensive news article was eye-opening… Thanks for the awesome article y’all :]

Nina Nguyen • Sep 23, 2021 at 1:57 pm

The topic itself is extremely relevant for students, and I greatly appreciate this article for shedding light on these unspoken issues within classroom environments today. The diagrams and charts were super effective!

Isabel Hoffman • Sep 23, 2021 at 1:51 pm

This article spread light on an issue I believe is covering our school and others. I agree with Ms.Schulz, and commend her for asking and being diligent when using students pronouns.

Adriana Samano • Sep 23, 2021 at 1:43 pm

I really enjoyed this article! I feel like the conversation about asking for pronouns needs to be more normalized.

Nicki Birangi • Sep 23, 2021 at 1:37 pm

The attention to detail here was really apparent and the entire article felt incredibly thoughtful. The care put into this made reading a very easy and enjoyable experience.

Nicole Rodil Suarez • Sep 23, 2021 at 1:32 pm

You did a really good job of incorporating the information you gathered from the survey into the story. It’s really cool how you used the interview with the teacher to also give insight into what teachers think and not just the students, giving multiple points of view.

Judith Carrizales • Sep 23, 2021 at 1:28 pm

I loved how you wrote this story. It was so informational. I loved how you provided photos in the middle of the article. Good job. 🙂