Shang-Chi: a superhero to fight the Asian monomyth

Marvel’s superhero movie Shang-Chi makes strides to break stereotypes of Asian-Americans.

As a fourth-grade Marvel fangirl needing a Halloween costume, I scoured the web for Asian superheroes. However, most of the lists resulted in obscure heroes that I hadn’t even heard of, so I eventually resigned myself to the ones already featured in the movies. Over the years, I’ve dressed up as a myriad of white characters, from Doctor Strange to Hawkeye to Scarlet Witch, so when Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings was announced at the 2019 San Diego Comic-Con, I couldn’t wait. This year finally marks the moment where an Asian superhero gets the spotlight.

From the movie poster alone, I could tell that Shang-Chi wasn’t going to be a typical Marvel movie. While it ended up having the expected smorgasbord of action, CGI, and pithy one-liners, the Asian main characters and supporting cast stood out from the previous 24 installments of the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU). It’s only the fourth major Hollywood film to contain a primarily Asian cast and the first Marvel movie to star an Asian superhero. As one of the stronger origin stories within the MCU, it also becomes a part of the larger conversation on what representation in movies truly means.

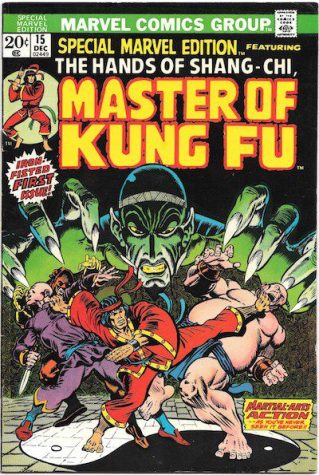

Before we get to the film though, it should be noted that Shang-Chi’s comic book history differs significantly from its movie counterpart. With his first comic appearance in 1973, Shang-Chi’s character was more a ploy for Marvel to jump onto the popular martial arts entertainment scene rather than an effort at inclusivity. The company wanted to acquire a license to the show Kung Fu, which was popular at the time, but failed to do so. Instead, it turned to the character, Fu Manchu, who was created by Sax Rohmer in the early 20th century. Fu Manchu was a racist caricature who fed into the idea of “yellow peril”, which painted East Asia as a danger to the West. This stereotype became Shang-Chi’s father in the comics, though his mother was notably white (perhaps to make sure that the audience wasn’t completely alienated). When American interest in martial arts faded, the comic was discontinued. While both the comic and the movie share the fact that Shang-Chi’s enemy is his father, the latter creates an original character, named Wenwu, who is much more complex and realistic.

Luckily, the movie doesn’t resort to hackneyed stereotypes. It begins with Mandarin Chinese narration, instantly transporting my thoughts to the Chinese dramas my mother loves to watch. Despite my somewhat tenuous grasp on the language, I could tell that the English subtitles weren’t the most accurate. For example, the narrator (Shang-Chi’s mother, Ying Li) says “huo shan”, which means volcano, but the subtitle for the word is nowhere to be found. Nevertheless, I appreciated that the movie included a lot of Chinese dialogue. So often, the Chinese heard on big screens comes from barely-decipherable, non-native speakers, so it was refreshing to hear the language that is spoken at my home unaccented in the theater.

While the beginning scenes deal with Shang-Chi’s childhood in China and his training as a ruthless fighter, it’s when we jump to modern-day San Francisco that more Asian-American cultural aspects unfold (though I appreciate young Shang-Chi sporting the quintessential toddler Asian haircut: the bowl cut). Even the city itself is relevant, as it is home to the oldest Chinatown in the US. After the time jump, we find an adult Shang-Chi, going by his American name of “Shaun”, and his best friend, Katy Chen, living their best lives as valets who stay out too late karaoking. The scene most relatable to my life is when Shang-Chi visits Katy’s family. The removal of shoes upon entering the house, parent pressuring about the future, and rice porridge on the table were all very familiar experiences.

Shang-Chi’s initial impetus for leaving his father and moving to San Francisco is the death of his mother when he was fourteen. This inciting incident reflects one of the movie’s major themes as a whole: grief. Wenwu is consumed by it, becoming a rampaging attacker who won’t stop at anything to get his wife back, even believing that she’s trapped in another dimension. Shang-Chi is the opposite, running away from the past while trying to ignore it. Even though Shang-Chi was raised in China, these opposing attitudes represent the East versus West mentalities toward death as well. This debate between holding on and letting go is also shown in the aforementioned scene at Katy’s house, where the American-born Katy questions why her Chinese-born grandmother continues to make offerings to her deceased husband. In the end, the movie tells us that neither Wenwu nor Shang-Chi were correct. Wenwu let the grief overtake him and blind his judgment, and it would have been healthier for him to accept that his wife was truly gone. On the other hand, Shang-Chi needed to remember his mother and channel her energy in order to tap into her skillset and connect to his heritage. This theme serves to highlight the complexity of differing viewpoints within the same culture.

Of course, a lot of the discourse surrounding this movie revolves around race. While there is a part of me that wishes we could simply focus on the merits of the movie, I have to remember that Hollywood is skewed against minorities, so race will become an intrinsic part of the conversation until that changes. Growing up, I was always pleasantly surprised when an Asian character popped up in media. I always rooted for them, no matter how small their role, and it wasn’t until I got a little older that I realized there was something wrong with this. The historical lack of Asian representation or flagrant misrepresentation in the media was baked into my childhood, but I hope movies like Shang-Chi prove that we’re heading toward a more diverse entertainment industry.

On the flip side, after watching some commentary channels, I saw some complaints that the movie wasn’t good enough representation. However, no one walked into Iron Man expecting to have the white experience captured, so it’s unfair to place so much responsibility on Shang-Chi’s shoulders. Perhaps, by raving how much I relate to it, I’m part of the problem, but I hope people recognize that Shang-Chi represents an Asian-American identity, not the only Asian-American identity. Upon first glance, the martial arts superhero might seem like a walking stereotype, but the vast array of Asian characters in the movie show that we are not a monolith. For Asian Americans who walked out of the theater disappointed, wishing for a closer connection to themselves, I hope they remember that there’s only so much nuance that can be placed within a two-hour movie. Because of their rarity, the Asian characters of Hollywood have an undue burden, but I was more than enthused about my culture’s reflection in Shang-Chi.

Beyond the Asian representation, I want to quickly highlight other strong aspects of the movie. While I’m admittedly not the biggest fan of action (I know, strange coming from a Marvel fan), even I have to agree with the critics that the combat choreography was breathtaking. The fight coordinators and actors worked together to deliver quite possibly the cleanest and most engaging fight sequences in Marvel history. Instead of the shaky camera work that has plagued modern action movies, the cinematography of Shang-Chi embraces the combination of Chinese Kung Fu styles like Shaolin, Wing Chun, and Tai Chi by not cutting every second.

The standout actor was Hong Kong legend Tony Leung (Wenwu). Despite being only 5’7”, every time he was on-screen, I felt intimidated. When people say the eyes are the windows to our souls, they’re talking about Leung. He has mastered the art of nuance within his eyes, bringing such depth to a character no one would expect to root for. I couldn’t help but feel sorry for him, even though he was responsible for the deaths of thousands.

Despite the pandemic and lack of release in China (for political reasons), Shang-Chi has managed to capture the country’s attention. It is the highest-grossing domestic movie of this year, and for good reason. The film isn’t perfect, and it follows many classic Marvel tropes (like the final act becoming an unremarkable CGI slugfest), but it still tells a heartfelt story that is worth two hours of anyone’s time. Besides the great acting and beautiful cinematography, Shang-Chi means a lot to me on a personal level. For the first time, the screen is focused on a hero who looks like me, and I’ve finally found a Marvel movie that my mother will understand.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Carnegie Vanguard High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs and fund field trips, competition fees, and equipment. We appreciate your support!

Hi, I'm Jessica! I am a senior and one of the Feature Editors for Upstream News. I love dance, Marvel, and cats.

Sofia Hegstrom • Nov 16, 2021 at 10:17 am

Yes ! You put into words so perfectly how I think a lot of Asian Americans felt about the movie. I really relate to what you said about the scenes in San Francisco– the part where they took of shoes hit so different.

P.S. hope Richard is doing well 🙂

Caitlin Liman • Nov 14, 2021 at 12:25 pm

This review really hit home for me. I admire the way you explained- well- everything! Adjusting expectation equality, illustrating sufficient history of Asian representation, and beyond, this article was exquisitely written, and having watched the spectacular just yesterday with my family, I can say that Jessica definitely did Shang-Chi justice :]

Nadia Talanker • Nov 9, 2021 at 2:16 pm

I loved this article so, so much. From the word choice to the actual comparisons, everything is so on point. As a Russian, I heavily relate to your commentary of Hollywood implementing only stereotypes in their films, and even now, I cannot name a single Hollywood or high-marketing film with a Russian that did not villainize or stereotype them. I hope that Shang-Chi is not only a step forward for Asian people, but for every ethnic and race group whom has been represented in an incredibly one-sided fashion since, well, forever.

Amazing article and I loved the balance between reviewing the actual film and the representation it offered! [:

Atahan Koksoy • Nov 9, 2021 at 2:16 pm

This story brings something more personal to a review of a multi-million dollar, blockbuster superhero movie.

Jahrel Noble • Nov 9, 2021 at 2:14 pm

This story is so well-done and the personalization done here is amazing. As someone who loved Shang-Chi, this review did a really good job of recapping everything and I love to see how impactful this movie was for the Asian community.

Brooke Ferrell • Nov 9, 2021 at 2:11 pm

This story was really cool! I loved the way you brought in so many different ideas while making them cohesive.

Nina Nguyen • Nov 9, 2021 at 2:09 pm

Jessica’s ability to put into words how I felt about the movie was incredible. As an Asian American myself, I definitely found this article to be highly insightful and loved the personal touch she incorporated in the review.

Hilary Nguyen • Nov 9, 2021 at 2:08 pm

This was really fun to read. I like how you dissected the movie.

Ankitha Lavi • Nov 9, 2021 at 2:06 pm

I really love how you talked about representation. And you are definitely right about stereotypes or misinterpretation of Asian characters…Your anecdote at the beginning highlights why a Marvel movie like this is so important!

Nicole Rodil Suarez • Nov 9, 2021 at 2:04 pm

You gave so much detail and explained the plot without giving spoilers, and the small moments you shared that you connected to was really good.

Danielle Yampuler • Nov 9, 2021 at 2:04 pm

I love this story. You incorporated so much of your own experience and that really made it special.

Abigail Nunez • Nov 9, 2021 at 2:04 pm

I really enjoyed reading your story, I really liked how you familirise yourself to the movie since it is the first Marvel movie featuring an Asian superhero .

Julian Namerow • Nov 9, 2021 at 1:59 pm

I loved when you compared iron man to this movie and how it represents race…that past was so good. You’re a crazy writer Jessica.