Op-Ed: The anti-hijab rhetoric is misplaced

Twitter, Quora, Al Jazeera (edits made by Manizeh Rahman)

Many Muslim women around the world are perceived as oppressed because of the intense coverage of terrorist groups and oppressive regimes in the Middle East.

On September 16, 2022, Mahsa Amini was killed by Iran’s morality police because, according to them, her hijab wasn’t being worn properly. This sparked protests throughout Iran and the rest of the world. Since her death, there have been calls to get rid of the Islamic regime altogether, citing that the mandatory hijab law for women currently in place is a violation of a woman’s basic right to choose.

This call has in turn become the fuel for virulent anti-hijab rhetoric.

On the same day, at a Baltimore high school, a 16-year-old Muslim girl was locked in the restroom by a staff member and beaten up by her peers. Her head was pummeled, and her hijab, forcibly removed, was used as a weapon to choke her. What this proves is that the hijab’s use of oppression in certain countries is wrongfully attributed to the religion and not the conservative culture surrounding it.

Historically, Muslim women as a group have been perceived as submissive, weak, and oppressed by their male peers. This wrongful perception of Muslim women comes largely through their portrayal in mass media. Often, when there is a Muslim woman in film, she is shown to be largely in the background or as a potential romantic partner. Additionally, if a Muslim girl is a lead, she is almost always abused by her authoritarian, conservative father as seen in movies like Hala or Secret Superstar.

For context, a hijab is a headscarf a Muslim woman wears to cover her head. It’s a way to practice modest dressing, since Islam requires modest attire for all its followers. There are many ways to wear a hijab. Some women wear a simple scarf around their heads, tying a small knot in the front or back. Others tack on multiple layers, securing the scarves with a few pins. There are even ready-to-wear hijabs, which are made of elastic polyester and can simply be pulled over your head.

Personally, I, Manizeh, don’t wear a hijab. My parents don’t enforce it, and I never felt the need to wear one outside of my prayers. My mother doesn’t wear a hijab either, and my father doesn’t force her to. My father often tells me how proud he is of my mother’s accomplishments. He often tells me how proud he is of my accomplishments as well. Additionally, he holds deep reverence for his late mother, who he always looked up to while she was alive, and he’s quite attentive to his mother-in-law whenever she visits us. In short, my father loves, cares for, and respects all the women in our family, which is an antithesis to the stereotypical abusive Muslim man the media often likes to show us.

Though I, Nicole, am not Muslim, I did live in Dubai when I was younger and experienced Muslim culture first-hand. I had a friend I was really close to who was Muslim, and one day, while at her house, I asked her mother about their culture. She didn’t wear a hijab and her husband was very loving towards her. He wasn’t “oppressive” or “abusive” towards his daughter, either. My friend had told me that she wanted to wear a hijab when she was older. Her mother and father were very supportive and told her she could wear it if she wanted to. If, after trying it, she found she didn’t want to wear it, her parents would continue to be supportive of her. It was her decision in the end. How she connected to her culture was her choice.

While we understand that wearing a hijab is not listed as a farz (requirement) by the Qur’an, Islam’s most sacred text, many non-Muslims mistakenly believe that the hijab is a religious requirement for women. Because of stereotypical media portrayals of Muslim women, the hijab has come to represent a symbol of oppression. These women are usually shown to be forced into wearing a hijab by their families. In the Spanish drama Elite, the Muslim girl removes her hijab towards the end of her story arc, representing her supposed freedom to finally be herself.

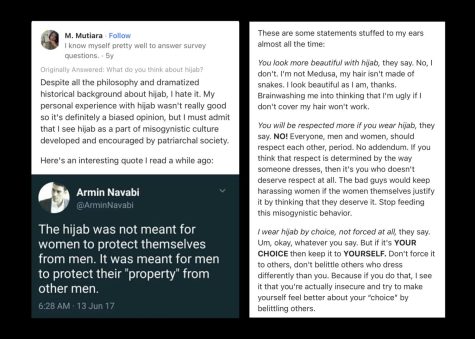

Muslim characters removing the hijab to be “free” is a very harmful representation of Islam. Families who force their women to wear hijabs often do so because of their conservative culture. Therefore, it’s understandable when a Muslim woman gets angry at a non-Muslim suggesting that they are oppressed because it’s assumed that they’ve been forced to wear the hijab they willingly chose to wear. Often, Muslim women and girls who willingly wear a hijab feel more like themselves when doing so, making it all the more frustrating to read posts on sites like Quora and Twitter decrying the hijab for its supposed misogynistic roots and oppressive nature. Not only is it frustrating, but it is also traumatizing to Muslims like me, Manizeh, who truly believe in their faith whether we wear a hijab or not.

Non-Muslims and ex-Muslims who decry the hijab emphasize that they’re not targeting those who willingly wear the hijab (though sometimes, they go the extra step and try to force others to stop wearing one). However, the irony here is that as they condemn the hijab for systemically oppressing women, they’re exposing their lack of knowledge on the difference between a cultural belief and a religious requirement, especially when it comes to Islam and its connection to conservatism.

Dissidents of the hijab fail to recognize that it is often used as a political tool—completely separate from religion—to force women as a whole to conform to a certain standard, using cultural sentiments as fuel to justify certain policies. This ties in with Mahsa Amini’s death by the morality police in September as well as the French policy which bans girls under the age of 18 from wearing a hijab and hijab-wearing mothers from accompanying their children on school trips. Whether it is forcing women to wear the hijab or banning women from wearing it, the common factor is the politicization of it.

To effectively combat this issue, we need to allow more Muslims to write their own stories. According to the study Missing and Maligned: The Reality of Muslims in Popular Global Movies, 39% of primary and secondary Muslim characters were shown as perpetrators of violence. This in turn causes Islamophobic stereotypes to be ingrained in the minds of non-Muslims, leading to an alarming rate of Muslims who are bullied at school or who don’t feel safe there as well as Muslims who may be harassed by their peers or colleagues. If there were more Muslim creatives who served as the captains of their own representation, then there would definitely be an overall increase in positive representation, and non-Muslims, ex-Muslims, and Islamophobes alike would be properly educated on how most Muslims think and behave.

Once, my father told me, Manizeh, that regardless of what someone’s religion is, it is the person’s character which matters the most. He went on to explain that if someone has enough hate in their heart to abuse and torture someone else, it doesn’t matter if they pray five times a day or fast every Ramadan, because those religious deeds are rendered meaningless in the face of their bad character. This is what you should realize if you do see a Muslim being hateful towards someone else or if you do see a Muslim woman being abused. Rather than let it act as a confirmation for your biases, assess the person based on their character—not the religion they profess to follow.

Whenever you see a piece of media that glorifies the hijab as a tool of oppression, think of the reasons why it has been portrayed that way. Think of the context behind this negative glorification. Think of why someone might want you to see the hijab in the way they’re portraying it. It’s very easy to educate yourself on what being a Muslim truly means. Just go to your local mosque, where an imam or another Muslim will answer all the questions you have.

Most Muslims are more than willing to share their religion with you—all you have to do is ask and keep an open mind.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Carnegie Vanguard High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs and fund field trips, competition fees, and equipment. We appreciate your support!

Manizeh Rahman is a senior at CVHS. In her free time, Manizeh enjoys watching K-dramas, making digital art, writing, and listening to music. She also loves...

Nicole Rodil Suarez is a current senior here at CVHS. Some tasks that she enjoys doing out of school are reading, specifically fiction, baking with her...

Lima • Dec 13, 2022 at 8:29 pm

What a great article! The authors shared their relevant personal experiences, giving meaning and depth to the sentiments conveyed. I will definitely think about this article next time I see a movie character presents in a hijab.

Dia Vaswani • Dec 13, 2022 at 10:35 am

I like how you started the story and took a strong stance. The development of this op-ed throughout is beautifully written and I love the personal connections which you made!