Op-Ed: “Whitewashed”: What makes someone Vietnamese enough?

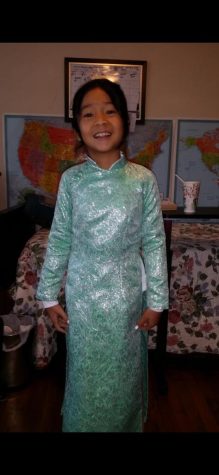

John Nguyen wearing a traditional Vietnamese áo dài next to his grandmother on Lunar New Year.

Piercing. Their glares held like daggers to our skin, prominent in the way they looked at us as if spotting two outliers. It drove our hatred for family reunions like these. How they’d engulf themselves in conversations across the table, throwing sideways glares at all the words they spoke and knew we didn’t understand.

Hushed whispers in Vietnamese as they’d clutch tightly to the plethora of drinks and foods arranged in neat rows across the table. They were always across the table. Maybe it was in the way we didn’t speak Vietnamese or how we weren’t born in Vietnam, but we always managed to be banished to the other side of the table. “Whitewashed” was the term our grandparents used. Meaning we’d lost touch with our culture, and by extension, with ourselves and the family.

In Webster’s Dictionary, “whitewashed” is defined as “an act or instance of glossing over or of exonerating something.” Though this is its definition, the term has adopted a newfound use over the years in a common context that is now used when saying that one is losing their cultural identity, or in my case, not being “Vietnamese enough.” So, how has perfecting something come to mean making it whiter, and more importantly in that light, how has anybody still viewed it as okay to say?

Whitewashing has been found by some to be rooted in art and history. For example, we see heroic figures like Jesus depicted as a white, blue-eyed man, even though he’s from the holy land of the Middle East. For others, it’s seen in our educational system, where information about the American Civil War has been focused on conflicts between states’ rights, rather than distinct efforts to abolish slavery. Finally, it’s been seen in the entertainment industry, where white artists were found singing songs originally written by black artists in attempts to make them “more suitable” for audiences.

It’s no surprise then that idealization and the idea of perfection has arisen behind things or people that are white. This change of definition can work to explain the normalization behind the term’s usage, as many have overlooked and diminished its impact because they may not yet be familiar with the word’s change in etymology. Additionally, sometimes, normalization simply amounts to ignorance.

I [Ella] have on countless occasions been called whitewashed as a joke. It’s essentially funny until it’s not. I distinctly remember when one of my friends said I wasn’t deserving of my last name, “Pham.”

“You’re so whitewashed,” she said. “It’s ironic your last name is Pham.”

This really resonated with me, as my name was one of the things I most identified with, and for someone to say I didn’t deserve its title evidently spiraled me into a state of distress.

“Calm down,” she said shortly after. “I was only joking.”

Joking is exactly the thing people have done to normalize the word and use it in marginalizing people of color, as it insinuates dissociation with one’s ethnic culture in replacement with “white culture.” Due to people often dismissing the term as a harmless joke, it’s evident calling someone whitewashed is a microaggression. Thus, like microaggressions, they’re small and subtle comments that could be perceived as innocent to some but are largely harmful to the person receiving the comment.

According to Pfizer, microaggressions impact mental health through behavioral patterns like depression, stress, trauma and anxiety and can even result in cardiovascular diseases. Moreover, a study done in 2019 strongly connected a pattern of microaggressions with shorter telomeres (the ends of chromosomes) among African American women in the United States. Additionally, a study done in 2015 depicts how students on campus feel tension due to microaggressions, causing them to actively experience more self-doubt, isolation and frustration.

This self-doubt is highlighted by creating the idea that one must prove themselves worthy of their own culture. But what about us makes us not worthy of being Vietnamese? We eat traditional foods, follow Vietnamese customs, participate in holidays and we have even visited Vietnam, but it’s clear to us that the people calling us whitewashed don’t see this. Instead, people are basing their cultural perception of others based on what they can see. They judge us based on the language we speak, the clothes we wear and our “Americanized” mannerisms.

Although we are first-generation immigrants and were not born in Vietnam, that doesn’t mean we don’t understand our roots, though they are something our language barrier has largely separated us from.

In order to prevent the term “whitewashed” from being used, people should educate themselves on how the term impacts others in things like mental health and understand the implications behind it. Amongst these implications is the underlying idea that people of a certain culture have to act and live in a certain way in order to deem themselves Vietnamese, which is not true. It’s time we become aware that there is no one way we should be asking people to prove themselves worthy of their racial identity, because there is no one way people of a certain race should behave.

People who use the term “whitewashed” may use it in a joking manner meaning no harm; however, no matter the intention behind using the term, it’s still offensive and ignorant. People of color especially should understand the ways in which being of similar ethnic backgrounds generates an important sense of belonging, as part of a common social group. Think about the ways that the term “whitewashed” ostracizes people entirely from any social group, as if people of color are not part of their culture and will never be perceived entirely as white; then what are we leaving them with?

Though we may have desired any implication we looked or acted white when we were little, we’re older now. We’ve learned to love our culture and take pride in it, as it’s become substantial to who we are.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Carnegie Vanguard High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs and fund field trips, competition fees, and equipment. We appreciate your support!

John Nguyen is a math-loving student and aspiring Doctor from Houston, Texas. He is from a Vietnamese household and wishes to visit Vietnam, as well as...

Ella Pham is a junior at CVHS. She is part of Carnegie’s Competitive Dance Team and has been dancing since 6th grade; her favorite type of dance is contemporary....

Neela Ravi • Dec 13, 2022 at 10:31 am

cool story! white-washing has definitely become a weaponized term nowadays.

Roxell • Dec 13, 2022 at 10:27 am

Great story you guys! Whitewashed being used as a joke is not a joke. It really sucks because when it comes to being born in the U.S., you can feel disconnected so much from your culture, so is it really the person or the society that makes one “whitewashed”?