“You can get the score that you want and that you deserve because now some of these boundaries are just a little bit more user friendly,” said CVHS World and US History Teacher Kristen Davis-Owen after changes for the CED (Course Exam Description) in the Document-Based (DBQ) and Long Essay (LEQ) Questions may have diminished pressure for North American AP test-takers in US, World and European History for (2023-2024) and further academic years.

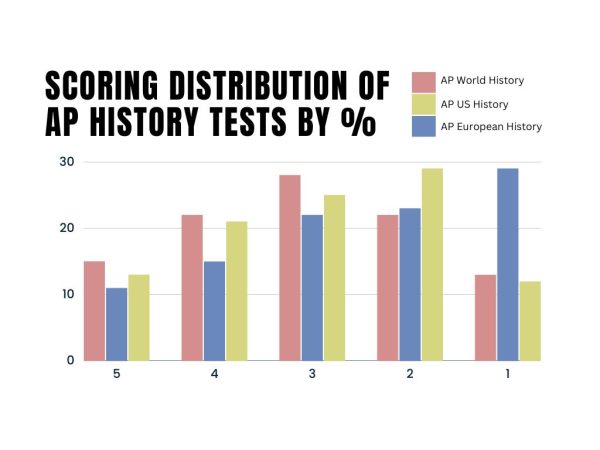

Previously, the AP History Tests have historically been the hardest to pass. This past year, pass rates and five rates for World, US and European History ranked in the lower third among all AP Exams, with US History reaching an all-time low of 48% passing. Now that the regulations for these tests have changed, we’ll delve into the exact changes the College Board addressed in their September announcement and gain insight from teachers around CVHS to view how this can affect the future of AP History.

One of the grandest changes in the DBQ lies in complexity points. Complexity was previously awarded for exploring different counterarguments and variables all sources pose throughout your essay. It’s known as the “unicorn point” among AP graders because of how rarely students earned it.

Davis-Owen even stated, “I read DBQs this past summer, [and] I had less than five students get a perfect score on a DBQ out of the hundreds that I read over the course of 11 days.”

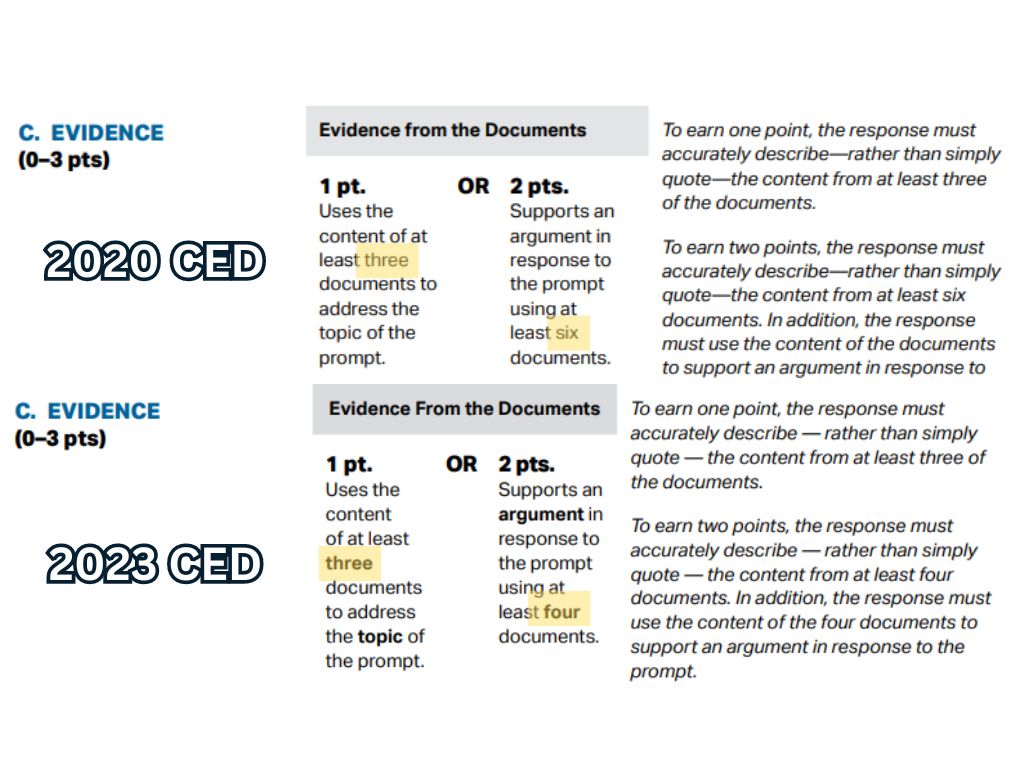

To add, the previous rubric made it extremely unclear how to score this point, and with the new CED stating that you can either explore numerous counterarguments, source four of the given documents (through the historical point of view, purpose, point of view, or intended audience) or simply cite all seven documents as evidence, we’re expected to see a big change in the upcoming test rubrics.

Another crucial modification to the new CEDs across the board regards the amount of evidence a student must source in their claims. Now, a DBQ can source a mere four documents to score both points for evidence from the document (or 3 documents for one point).

Compared to the six documents needed last year to score points, “I do think more kids will get the second evidence point,” explained Jane Schulz, an AP World and AP European History teacher at CVHS.

Some may think this change was made over the summer for teachers to plan ahead, but according to Davis-Owen, “We had no idea it was coming… they (college board) haven’t been super clear about their rationale”

However, by taking inferences from changes similar to the 2015-2017 changes (where all AP History tests shifted to a conformed test layout) made to the AP histories we can come to attribute the revisions to scoring both as a whole and compared to the previous testing year.

Although the cause of the change hasn’t been explicitly stated, Schulz suggested modifications were made in students’ best interest, “they [college board] want to have more pass rates.”

College Board is trying to find ways to make points more attainable but still have students utilize the same skills as before. The low scoring distribution mainly applies to AP US History(APUSH), but due to the 2015-2017 implementations, all of the AP histories must abide by new scoring regulations.

The other major concern from College Board we can speculate on is the comparison between the Class of 2025’s score distribution in World and US History. While the curriculum of both tests varies, where World History is based on connections and US History is more detailed due to a shorter geographic area and period, the layout of each test is nearly identical. Davis-Owen accentuates this point and how the recent APUSH exam may have been a disservice to the sophomores who couldn’t have lost all of their skills from World History.

—

These changes impact students around the world learning the American curriculum. Schulz makes an interesting point in “our [Carnegie] kids do well on the DBQ… the DBQ averages globally have been high two to something low three to something and we’re usually closer to like low four or high four.”

The scoring distribution will likely have a less drastic change at CVHS, especially because scoring is based on relative performance and not a raw score.

Additionally, it’s possible College Board “in exchange for requiring less sourcing statements, they now are going to be more picky about them,” according to Davis-Owen.

While gaining those first points may become easier, the overall strictness of the rubric is to still be determined. For now, it looks as if the CVHS History teachers are teaching about the same or higher level of quality.

Davis-Owen also makes an interesting point about students whose first language isn’t English in regards to the test, where “what you’re [College Board] also accidentally assessing is how quickly a student can read… decreasing the ability of students for whom English is not their first language. And who can be incredibly intelligent but needs a little bit more time to process those documents that are all in English of course.”

With fewer sourcing statements and evidence points, students can focus more on the quality of their essays rather than the amount of evidence and sources they need. Furthermore, for students who are less keen on analyzing the documents for historical context and author’s purpose, having the option to cite seven sources can prove beneficial.

Lastly, new scoring changes always come with responses from colleges around America. Davis-Owen makes a keynote about how “[universities] argue constantly about whether or not they should be giving college credits to students who pass this test,” and though college classes are more asynchronous with final exams while being weighted extremely heavily, have less content and tasks than the AP.

We’ll have to see in a couple of years when current juniors start college applications whether or not the AP Histories will be less valuable to individual colleges and the Common App.

—

Overall, these rubric changes may alter the landscape of History AP exams to be more user-friendly in general, particularly when it comes to time management. However, the AP exams shouldn’t be seen as the sole measure of a student’s potential or success.

Even as an AP teacher and grader, Schulz recognizes “AP is not the end all be all… even if a kid doesn’t pass an AP exam, being exposed to that level of content and those skills is valuable for later classes in college”.

Even if you don’t achieve your desired score, the experience gained from practicing with such challenging material can prove to be an asset in the future.

“All of these goals are achievable,” Davis-Owen says, “so yeah, never give up.”

Hector Morales • Dec 7, 2023 at 1:13 pm

Interesting World History now is a piece of cake.