The Kids’ Online Safety Act is currently under consideration in the Senate. The bill, coauthored by Senator Marsha Blackburn (R-TN) and Senator Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), has both support and opposition from both sides of the political spectrum and authoritative organizations; rarely can it be said of a bill that the American Psychological Association approves of it and the American Civil Liberties Union doesn’t.

KOSA is an attempt to solve the “teenage mental health crisis in America” by holding social media sites responsible for “prevent[ing] and mitigat[ing]” such wide-ranging problems as eating disorders, depression, anxiety, bullying and sexual exploitation. It wants platforms to do this by filtering and limiting what young people are allowed to see and plans to enforce this by giving state Attorneys General the power to sue sites for letting young people see whatever those AGs deem dangerous.

The first version of KOSA was introduced to the Senate in 2022, giving any platform “used, or reasonably likely to be used, by a minor” a “duty of care” to reduce certain undefined harms to children by not letting minors see certain content and making those platforms liable to be sued by state attorneys general should minors encounter it. In addition, it would compel platforms to provide data to researchers, require age verification to identify who is and is not a minor and give parents the power to block or filter the content their children see.

For example, let’s take a fictional boy, Johnny, who lives in Texas and uses TikTok. Johnny is a trans man but doesn’t want to tell his parents. He also has anorexia, not uncommon among trans youth. Under 2022’s KOSA, his parents would have access to information about what content he had viewed on TikTok, to which he would have to give revealing personal information (at least his date of birth, probably also legal documents backing this up). If he engaged with, or was fed by the algorithm, any content concerning the LGBTQ community, eating disorders, or transgender existence and life, his parents would find out and would have the power to stop the platform from recommending Johnny videos concerning the queer community and anorexia, or from talking to friends Johnny might have made on the platform, without Johnny’s consent or even knowledge; if they brought it to the attention of the state, Ken Paxton might well sue TikTok for this boy’s anorexia and transgender identity. This provides an incentive for TikTok itself to limit the visibility of content concerning the queer community or eating disorders, including eating disorder recovery.

In November of 2022, the Electronic Frontier Foundation sent an open letter to the Senators, detailing their complaints about the requiring of invasive age verification and parental controls, incentivizing of user surveillance and over-moderation, and the ability it provides for state Attorneys General to decide what kids in their state can and cannot see. The letter was signed by organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union, Transgender Education Network of Texas and the Yale Privacy Lab.

In May 2023, Sens. Blackburn and Blumenthal reintroduced the bill to the Senate, with some changes, such as not explicitly requiring age verification on sites (but still requiring that social media sites not serve ‘dangerous’ content to users they ‘reasonably should know’ are minors), and requiring sites to regularly audit themselves to see how well they protect users’ privacy. The bill still puts the power to decide what about the ‘designs and services’ of social media and communications sites are dangerous to minors in the hands of the Federal Communications Commission and 50 state attorneys general. It still gives parents direct control over what their children up to 16 see. There would be no change for Johnny. The bill got out of committee by Aug., with many Senators behind it.

On Feb. 1, 2024, the Senate held a hearing on online child safety, speaking to the CEOs of Discord, X (formerly Twitter), Tiktok, Meta and Snapchat. Many teenagers listened to the closed hearing via a Discord server, and shared their opinions on it, most disapproving. The bill currently lacks a counterpart in the House, a potential block to passage.

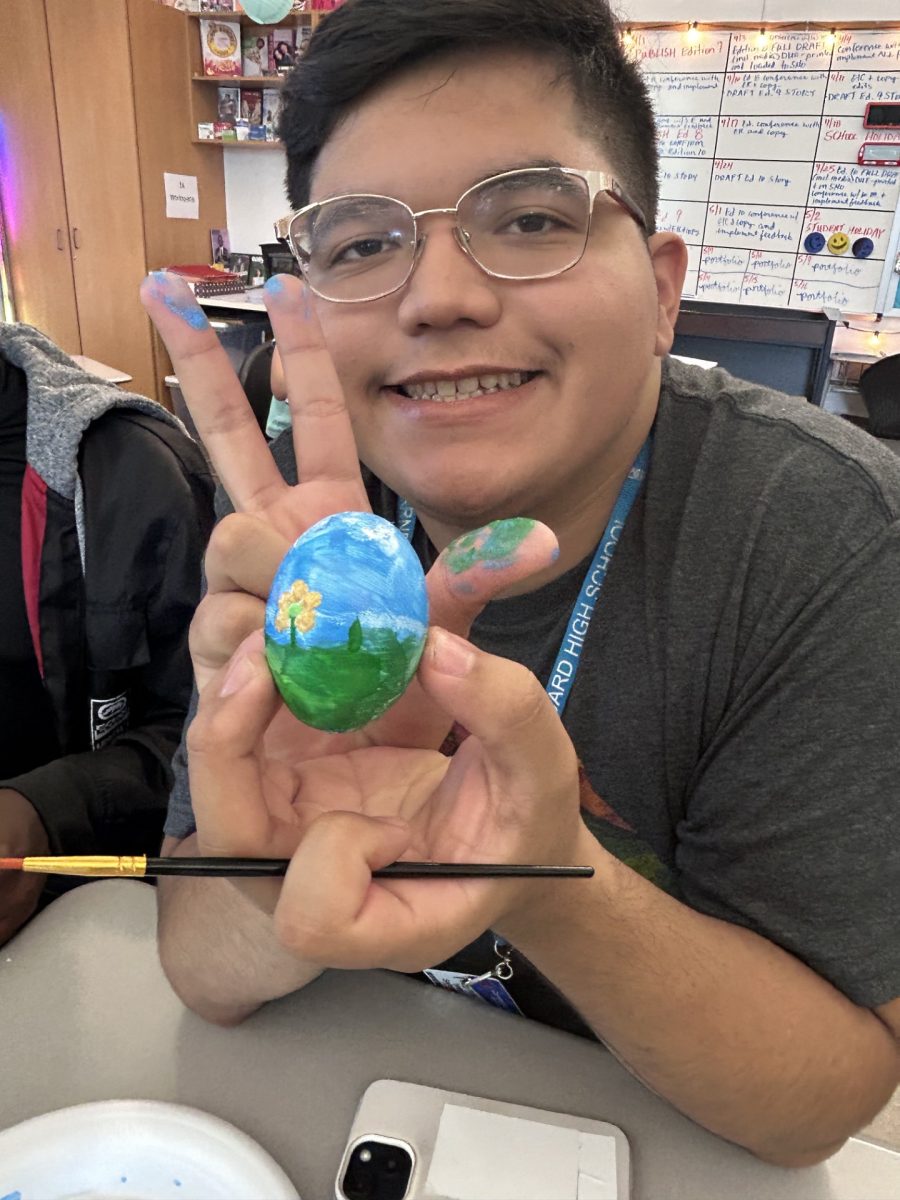

Our own GSA isn’t much of a political actor; LGBT+ students come together to have a safe space, according to Mr. Parker, who sponsors the club. The GSA does do some days of action, as with their Coming Out Day event earlier this year, but they don’t make concerted efforts for political ends.

KOSA’s threat to free speech is clear. It threatens international social media platforms with litigation from US state Attorneys General if minors in America encounter anything that those individual state AGs think those minors shouldn’t see. These things include “the transgender in this culture”, according to Senator Blackburn (who also apparently thinks education on America’s history of racial discrimination is dangerous to children), as well as Tiktok “being used to basically destroy Israel”, according to Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC). These comments at the hearing are just one example of how rife for abuse KOSA is; these senators’, or at least their comments’, the problem with social media was less the harm it can do to people of all ages and more than ideas they didn’t like are being circulated on it, and part, or all, of what they see in KOSA is the potential to stop those ideas from being circulated. The right-wing Heritage Foundation also complains that “gender ideology” isn’t explicitly in the list of harms the 2022 KOSA is supposed to prevent, making KOSA sound less like something that will protect children under 16 and more like a book ban campaign on steroids. Voices further to the left, like the ACLU, warn it “would make kids less safe by cutting them off from access to lifesaving information and resources on controversial but important topics”, according to Evan Greer, director of the nonprofit Fight for the Future. This bill encourages social media platforms to either collect data on their users even more invasively than they already do or block discussion of almost any sensitive or controversial issues, like reproductive rights, racism, the wars in Palestine and Ukraine, the existence of queer people, sex education (a not-uncommon use for the Internet) and any other contentious issues that appear in the coming years. It has great potential isolate to queer and mentally ill children, as well as victims of child abuse, stopping them from connecting with others and getting help by putting their engagement with the Internet fully under the power of their parents.

It’s still in the Senate, and we have yet to see what a corresponding bill may do in the House.