You had done everything you could to prepare for this concert: you’d listened to the artist’s entire discography four times over, which is four more times than you’d passed an AP Physics C exam; you’d vivaciously stanned the musician on X, formerly Twitter; and you’d memorized every lyric — now knowing more sick rhymes than you did AP Macroeconomics.

However, there was one thing you hadn’t prepared yourself for — modern technology.

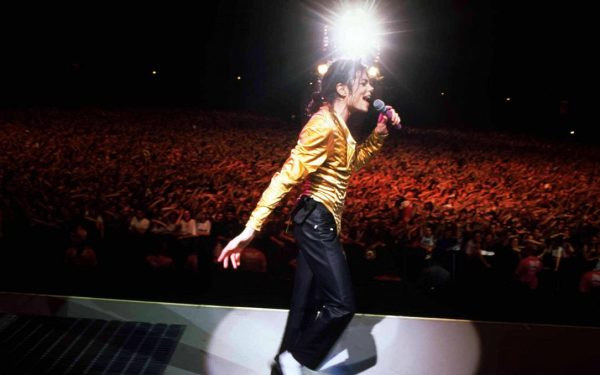

Just as the artist perambulated on stage in some glittered get-up, tens if not thousands of phones shot up toward the ceiling of the concert hall. You were immediately caged in — not only by sweaty, motionless bodies but also by iPhone 13s large enough to obscure the view you’d meticulously diagrammed and plotted hours in advance.

As you spent days preparing for this concert, immersing yourself in educational videos like “How to Enjoy a Concert in 10 Easy Steps” and “Moshing: For Dummies,” there was one thing you hadn’t checked: the year they’d all been published — 2009. Oh, barnacles. In that time, concert culture had long since been laid to rest.

Concert culture refers to any of the trends, customs and “lifestyles” revolving around live music. It often encompasses aspects such as audience interaction, venue atmosphere, performance etiquette and social norms. It can vary significantly depending on factors like music genre, location and the demographics of the audience. For example, you won’t see moshing at the upcoming Hozier concert, unless you take the initiative to #startmoshing at #Hozier #concerts.

Regardless of the lack of moshing at non-metal concerts, all live music performances were once notorious for the life they brought from both the crowd and the musicians themselves. In recent times, that aspect of concert life seems to have disappeared in lieu of memorializing the concert through videography.

Except, the memory aspect of memorializing the experience of a concert is nonexistent, considering people are more focused on taking videos than living in the moment.

“I’m really here, in real life, [for you] to enjoy, in real life,” Singer Adele said at one of her concerts in 2016.

Prior to her denouncement of phones at her live events, Singer Mitski tweeted, “When I’m on stage and look to you but you are gazing into a screen, it makes me feel as though those of us on stage are being taken from and consumed as content, instead of getting to share a moment with you.”

Due to the growing trend of recording concerts, some artists took the initiative to ban phones entirely in order to preserve live concert viewing pleasure for everyone. Bruno Mars, for example, became one of many artists to collaborate with the company Yondr during a concert of his in 2018. Yondr works to create “phone-free spaces” by physically locking away users’ cell phones.

Many audience members appeared to enjoy the change, reflecting on the situation: “At first was annoyed (no IG stories) but loved watching the entire place unplug and enjoy being in the moment. Singing and dancing with the energy from the room,” tweeted one crowd member.

However, you haven’t been so lucky. After your concert was quintessentially ruined, you go home, naturally. I would hope you go home. You settle onto your couch and scroll through your phone, a routine you’ve repeated countless times before. You find yourself alone with the same device that dismantled your anticipation for an experience you had eagerly awaited for months, just hours earlier.

That’s when you see it for the first time — the concert you want to go to.

There are twenty different angles of the stage, forty fan cams of the artist, a POV from 60 individual phones that were thrown onto the stage and even a wide-angle video from a drone in which you can be seen sobbing in the crowd. Every member of the audience around you is solely engrossed in their phones. Comparing these videos to the older ones you’d researched, dating back 10 to 15 years, you observe a stark difference in how distracted and apathetic this crowd appears.

Those who do participate in the concert physically beyond artists’ crowd work have been reported as acting inappropriately and dangerously in growing numbers.

28.8% of pop concert attendees reported sustaining an injury while at the concert. Audience members face various dangers, including overcrowding, physical assault and the risk of objects being thrown into the crowd. In some cases, these hazards can lead to injuries such as bruises, cuts, or even more serious harm. According to the National Library of Medicine, the most common injury for audience members was contusion.

Additionally, several artists have faced violence during their concerts. Bebe Rexha was struck in the face by a phone, Drake was hit in the arm by another phone, Harry Styles had Skittles (among other objects) thrown at him in 2022 and a fan tossed their drink at Cardi B in 2023, which the singer retaliated.

These instances highlight the extinguishment of concert etiquette and emphasize the urgent need for change as a range of artists prepare to perform in Houston during April and May.

Ensuring that audience members are aware of how to behave not only enhances the enjoyment of the concert experience for everyone but also fosters a respectful and inclusive atmosphere. By promoting awareness of concert etiquette, we can contribute to creating memorable and enjoyable experiences for all. Go forth and freak.