The ‘masquerade’ as many a senior would recognize it, with mystery, flouted social norms, wild parties, and glamour began as the Venetian festival of the Carnivale. In medieval and Renaissance Venice, Carnival stretched from the Christmas season to Martedì Grasso, or Fat Tuesday, the last day before the Lenten season of control and sobriety. This was a citywide festival, where almost all of the population put on some type of disguise and partied it up as hard as they could, taking advantage of anonymity to flout social norms; wealthy women walked unaccompanied through lower-class neighborhoods, the poor acted in parody of the rich, and the great draw of the masquerade was the anonymity of it all.

Having encountered the Venetian masquerade, the Swiss Count Johann (or, in English, Jon) Heidegger held the first ‘masquerade ball’ in England at the Haymarket Opera House in 1710, five years before the first recorded masquerade ball in France. These ‘carnivals behind closed doors’ remained popular through the eighteenth century in England, but didn’t catch on in France until the building of the great thoroughfares which linked the rich and poor in the 1820s.

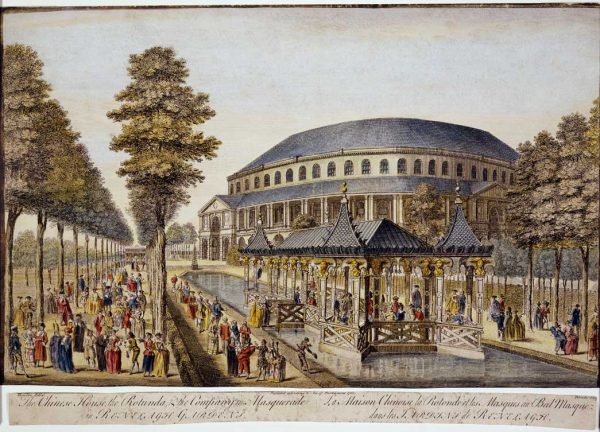

Masquerades were immensely popular, and not just with the upper classes. Though purchasable tickets to ‘public masquerades’ tended to be expensive, the venues, such as London’s pleasure gardens and Paris’ theatres, were full of raucous partying. In England, some were staged for very special occasions, such as royal birthdays or the end of a war; the 1749 masquerade in Ranelagh Gardens in celebration of the end of the War of the Austrian Succession was said by politician Horace Walpole to be “the prettiest spectacle that ever I saw”.

The costumes Walpole would have seen came in great variety. The costume most iconic to masquerades is the Domino, with a face-concealing Bauta mask and a large black cloak over the body. More specific costumes were usually cultural references. Two other main categories of costumes seem to have existed: “fancy dress” that imitated some group, like when upper-class ladies dressed as milkmaids, or the stereotypical ‘national costumes’, especially of English colonial possessions, that were popular; and “character dress” that imitated some specific figure. In keeping with the ball’s Italian roots, Commedia Dell’Arte stock characters like Columbina, who gets her own mask, were popular, as were Greek mythological figures, historical figures, or allegorical representations of ideas. Death and Night were frequent guests, and in 1788, Mrs. Egerton’s costume as Curiosity made “her company both coveted and dreaded”.

Masquerade balls, owing to the anonymity of the attendees, were sites for the flouting of social rules. The aforementioned Domino costume was worn by all genders, and in 19th century Paris, one of the most popular costumes for women attendees at masquerades was the ‘Débardeur’, an open-shirted dockhand. Balls like this caused anxiety among the upper class as well as moralistic clergy and writers; the risk that one could speak and associate unknowingly with a member of the lower classes, or even a prostitute, was high in their minds, and if respect could be gained and lost as easily as taking clothes on and off, then that put the whole social structure of nobility and commoners into question. But that was part of the thrill; the point was to get dressed up as Truth, or Hera, or Robin Hood, or a wolf, and party all night long. Who knew if the lovely Lady Summer one danced with was a fine baroness or a prostitute, or if the kind friar with whom one shared a drink was, in the daylight of tomorrow, a dastardly criminal? Sexual freedom was also a part of this temporary destruction of the rules; women could act aggressive and domineering without fear of being labeled ‘unladylike’, or flirt however much they wanted, or, of course, dress in men’s clothes. Masquerades in the popular imagination were associated with the breakdown of societal mores, leading also to their use in the developing literary form (in the 18th century) of the novel as a set piece, often to test a character’s virtue and “dramatize a larger cultural conflict between moralistic and transgressive imperatives”.

Despite the general devil-may-care atmosphere of drinking, dancing, anonymity, and drawing mustaches on kings’ busts, masquerades still had a few rules that applied only there. Partygoers began conversations with specific phrases, like “Do I know you?” Costumes were, of course, absolutely required for admittance, but there was also a designated time for the guests to take off their masks, usually either midnight or dawn; sometimes for the very late supper meal, as some masks were impossible to eat in.

In the end, the decline of the masquerade ball came long before the decline of the aristocracy. In England, the masquerade balls that were so popular in the eighteenth century wound down with the nineteenth century’s stronger public moralism, but the anti-masquerade movement didn’t win completely; they survived as the less risqué ‘fancy dress balls’, one of the most famous of which was held in New York City in 1883 by the Vanderbilts. Mrs. Alice Vanderbilt, wife of Cornelius Vanderbilt II, attended dressed as ‘Electric Light’, and her costume (which did light up!) is still in the Museum of the City of New York. Since 2011, the Palace of Versailles has held masquerades on a Saturday in June, with tickets available for purchase; guests do have to remain masked all night long. And, of course, the Class of 2024’s senior prom is masquerade-themed. I wonder if we’ll meet Death, or Time, or Senioritis.