From Saigon to Kabul: Lessons We Haven’t Learned

Photo courtesy of Sofia Hegstrom

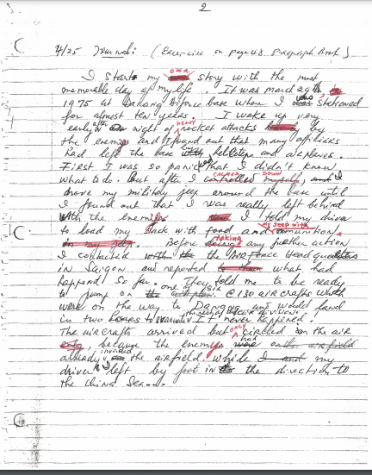

My grandfather Do Huu Nho in 1973 served in the South Vietnamese Air Force in U.S.’s war against North Vietnam.

March 29th, 1975: the first day of North Vietnam’s campaign into the crucial central city of Danang, following the American withdrawal of troops. My grandfather, who was stationed with his regiment at the Danang Air Base, had known for days that the enemy was approaching. With his wife, my grandmother, and his four children safe in Saigon, he was prepared to die at his post. The subsequent siege, escape and hysteria which ensued was carefully recorded in his diary, in the hopes that future generations could witness and learn from the horrors he survived.

The United States withdrawal from Afghanistan, which has now officially ended, and the subsequent humanitarian crises have left many Americans feeling angry, confused, and helpless. For Vietnamese Americans, however, the tragedy of the withdrawal and its human cost cut even deeper.

“ (The plane) looked like a honeycomb which was covered with bees. The aircraft was roaring to take off but they could not shut the door because it was full of people. It started to roll its wheels but many people were still on the top and wings. The pilots didn’t want to be hit by enemy rockets and they had to take off in that horrible situation.”

This is an excerpt from my grandfather’s diary account of his escape from Vietnam, but without context, it could very well be a report from the Kabul airport.

My grandfather, Nho Do, was a South Vietnamese Air Force officer based at the Danang Airbase, the second busiest and largest airfield in the country at the time. On March 30th, 1975, as the Viet Cong crept closer and closer to Danang, my grandfather was assured by his superiors that they would all stand their ground and fight. The next morning, woken by the blasting of enemy rockets, he found himself to be completely and utterly abandoned by his superior officers.

“The night of terror came and those who declared (their intention) to stay had left before the sunrise.”

Abandoned: This is how many Americans feel after we left Afghanistan, leaving in our midst scores of Afghan allies and American affiliated workers– not to mention the dozens of helicopters, attack planes, and weapon-stocked army bases. For many older generation Vietnamese-Americans, including my grandfather, American abandonment is a sticky issue.

“If we start being angry at the United States now, we will never stop.”

The United States, after all, is the country that took in nearly 150,000 Southeast Asian refugee. The U.S. offered refugees safety, shelter, and most importantly to my grandparents, an education. Many of us who were born in the United States have grown up with the constant reminder of the privilege of our American citizenship, especially when juxtaposed with those who were unable to escape.

My mother, who was nine when Saigon fell, grew up grateful for the opportunity America offered.

“You knew people were dying to flee Vietnam. Growing up, we had this feeling we were the lucky ones.”

But, when it comes to the withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan, my mom feels differently towards the United States.

“I feel angry in the sense that there was no thought put into the pullout for anyone else besides the Americans. What about all the Afghans who worked for you. Who helped you? They’re going to be left there, and they’re going to be massacred.”

Leaving Vietnam, for many refugees, was a chaotic, rapid exit that was filled with confusion and uncertainty. At the time, no one knew what would happen under communist rule, but every South Vietnamese feared for their life.

Here’s what really happened during North Vietnam’s final campaign: 120,000 South Vietnamese soldiers were massacred and captured in Hue and Danang (the city my grandfather narrowly escaped by boat). My grandfather’s younger brother Tung was one of these casualties. Here, my grandfather describes leaving Danang for the last time.

“My younger brother who was a marine regiment commander was still somewhere near the South of the city. Like me, he was left behind with his troops. The last word I heard (of) him was he got killed in action. Someone said he committed suicide when he was captured by enemies … Others said his uniforms were found on the beach after the enemies occupied the area. Night was falling on the ocean… my lovely hometown began to disappear in the darkness. I kept looking in the direction of Danang until I could see nothing.”

![]() Some estimate that up to a million of the surviving soldiers were sent to the infamous ‘re-education camps’, where imprisonments ranged from weeks to decades. After the Fall of Saigon, it is estimated that nearly 30,000 American-affiliated Vietnamese were murdered, hunted down by the communist regime after their names were found in the American embassy.

Some estimate that up to a million of the surviving soldiers were sent to the infamous ‘re-education camps’, where imprisonments ranged from weeks to decades. After the Fall of Saigon, it is estimated that nearly 30,000 American-affiliated Vietnamese were murdered, hunted down by the communist regime after their names were found in the American embassy.

This is the trauma and context Vietnamese-Americans have lived in the shadow of. For many Americans, the first images that emerged of the chaotic and desperate scenes at the Kabul airport were evocative of the Fall of Saigon. For those who have a living memory of the war, who watched with their own eyes as their cities, homes and ancestral lands were conquered and pillaged by the enemy, the gut-wrenching familiarity of the recent images of the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, is too much to bear. Both my mother and grandfather shut off the TV when scenes of Afghans plummeting from planes and children handed over airport fences were displayed.

On August 15, Secretary of State Antony Blinken said of the American withdrawal, ‘This is not Saigon.’ He’s right in many ways. Not only are the geopolitical contexts and premises of America’s two longest wars starkly different; the withdrawals are as well. The United States had already begun withdrawing American troops in a process known as ‘Vietnamization’ by the late 1960s. By the beginning of 1972, nearly half a million US personnel had already left. The Afghan forces, by comparison, folded much, much faster than in South Vietnam.

However, to those who lived through the war and younger generations alike, their disastrous endings feel the same. The United States entered both Vietnam and Afghanistan as a meddling savior, but left in our wake millions of victims, two countries and populations in complete turmoil. Twice now, the answer to our American-brand interventionism has been hopeless ends to seemingly ceaseless foreign wars. As any Vietnam War refugee will tell you, there are no words to describe the pain of losing a country, or, as in my grandfather’s case, watching it burn before your eyes. With the American withdrawal concluding on August 30, 2021, the Taliban’s complete takeover following shortly after, and an estimated 250,000 American affiliated Afghans left in the country, Vietnamese Americans are left with one question: When will we learn our lesson?

Your donation will support the student journalists of Carnegie Vanguard High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs and fund field trips, competition fees, and equipment. We appreciate your support!

Howdy! My name is Sofia Hegstrom and I am a senior who loves to read.

Pulchérie Gueneau • Oct 6, 2021 at 7:36 pm

Beautiful story, Sofia!