On the Legacy of Texas Artist Buck Schiwetz

“I hope I might have given Texans a worthy depiction of their great heritage and might have made them more aware of the need for preserving many beautiful old structures that will otherwise fall victim some day soon to the blind bulldozers of progress.”

When Buck Schiwetz wrote this, the Shamrock Hotel, Foley’s, Jefferson Davis Hospital, and the UH Robertson Stadium were still standing. The Astrodome was still used by the Astros. The Downtown was much smaller, and contained many buildings from the early 1900s and the late 1800s. In 2022, that has all changed, and almost all of these buildings are gone, while many more are at constant risk of destruction, making his work even more relevant…

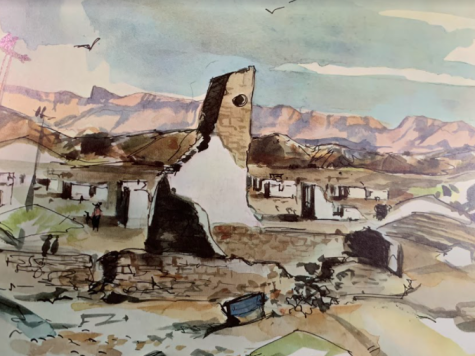

Buck Schiwetz was born in 1898, in a small town called Cuero. He grew up in the turn of the century, around rural scenes and old buildings. As he got older, his interest in art grew, and he was encouraged by his teacher and his mother, who was an artist, but not by his father, who wanted him to become an engineer. Schiwetz studied at Texas A&M, initially in engineering, but later switched to architecture. He later worked in the burgeoning field of advertising, first moving to Dallas, then to Houston. In the 1930s, his work began to receive recognition, winning the MFAH purchase prize in ‘33. Then, for the rest of the century, he traveled all over Texas, making sketches of historic buildings, farms, wildlife, and industrial areas for a multitude of organizations, including Humble Oil. The buildings he painted often became landmarks and were saved from destruction. Throughout his career, his style changed, but his subject matter did not. He became famous for his artwork, exhibiting in places such as the Art Institute of Chicago and the MFAH. He died in 1984, after a long career of traveling and painting.

Today few examples of his work can be found in public spaces. Most art museums in Texas do not display his work, even though paintings by Schiwetz are held in the collection of the MFAH and the Dallas Museum of Art. To many, it probably would not make much sense to display those works either. Scenes of traditional houses and farms seem awfully conservative and kitschy in museums that display modern and conceptual artworks that challenge artistic norms. But to tell the truth, Schiwetz’s work is not kitsch. It’s not nostalgia for a bygone era. Instead, as a whole, it is a massive project that documents a disappearing history and way of life in a state developing too fast to notice what it’s losing…

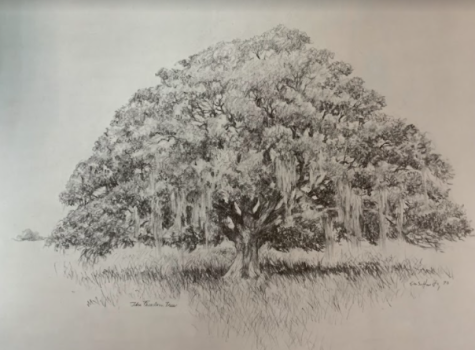

Some of Schiwetz’s works have been more successful than others in preserving their subjects. The Noble House, for example, which he sketched in 1959, is now a cornerstone of The Heritage Society in Downtown Houston, and he’s been well restored. The subject of another pencil sketch, the Freedom Tree, has also survived, and is now located at the Freedom Tree Park in Fort Bend County. Of course, many things have changed. That is another reason Schiwetz’s work is so significant. When The Freedom Tree was made by Schiwetz in 1970, the area was rural. It was grassland, with many other live oaks. Now, it is a highly developed suburb, with all of modern life’s conveniences: strip malls, massive houses, schools, fast food restaurants, and golf courses.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Other structures have not been so lucky. The Houston County Courthouse in Crockett, which Schiwetz painted in oils, is now long gone, and so is a rather striking house in Downtown Houston he painted in 1953. These structures were either destroyed by their city’s relentless hunger for land, or by modernization efforts. Some of the only surviving images of these buildings are those created by Schiwetz.

Lastly, Buck Schiwetz’s work is still significant in Texas because of its ability to illustrate the diversity of this state. He painted or sketched almost every corner of the state, often using different materials. Some paintings, like the one of the Houston County Courthouse, are from his “oils” era, while others are in watercolor, pencil, or oil pastels. There are paintings of scenes in Cuero, Houston, Brownsville, San Antonio, Fort Worth, Austin, Eagle Pass, Fredericksburg, Terlingua, Sterling County, and many more places. In short, in his portfolio, you find the kind of Texas that was very easy to see once; one that is still there, although it is disappearing rapidly. The question is, do we want to save it?

Your donation will support the student journalists of Carnegie Vanguard High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs and fund field trips, competition fees, and equipment. We appreciate your support!

I love reading, learning, drawing cartoons, watching films, and discussing art, history, politics, and business. I also collect historical artifacts,...