Thi Bui’s ‘The Best We Could Do’ shows the scope of the Vietnam War

Thi Bui’s debut graphic novel documents the life of her family during the Vietnam War and their eventual move to America.

I am a rather simple reader; if my favorite comedian recommends a book, I will read it. Among Ali Wong’s six summer book picks was Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do. I had originally intended to read it over the summer. However, after I discovered the premise of the book, I decided to save it for the end of February – around the time my parents immigrated from Việt Nam to America 30 years ago.

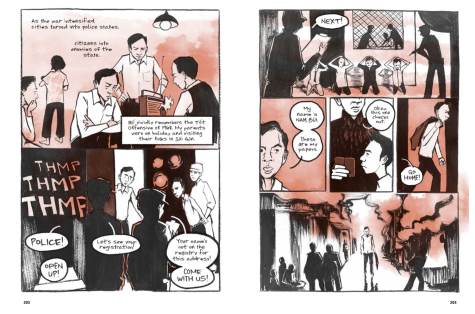

Published in 2017, Bui’s illustrated memoir follows her family’s upbringing in Việt Nam, their escape from the country following the Fall of Saigon, and the rebuilding of their lives in America. An American Book Award winner, Eisner Award finalist, and National Book Critics Award finalist, The Best We Could Do is a book about war and immigration at its core. Her family’s struggles depicted in the memoir reflect the ongoing turmoil within Vietnam and the pain it brought to citizens, from French imperialism to communism.

While this is Bui’s memoir, she appears to only be the narrator and a recurring character. Instead, her parents and their experiences growing up during Việt Nam’s attempt at liberation is the focus of the memoir. When writing about her parents’ lives, some events are not in chronological order. This detail was something I overlooked initially, but when I noticed it, the book became rawer. Bui’s meandering of time reminds readers that the chronology of memories is personal.

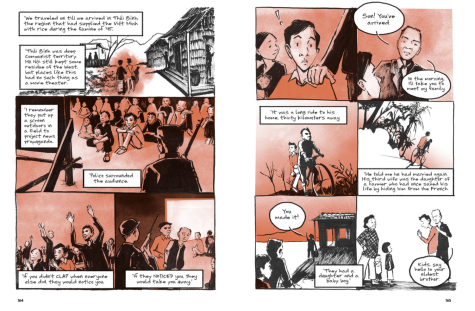

The intricate details Bui weaves into her writing make readers appreciate the art of expert storytelling. Bui recounts the time her father passed through Thái Bình when visiting her grandfather. There, he was forced to sit outside in front of a makeshift movie theater and listen to communist propaganda. When I was reading this page, I could feel the fear Bui’s father and the crowd felt as police watched them clap emptily at the messages playing. It is the same feeling I felt when my father first told me about my grandfather’s experience in a communist re-education camp in Vietnam. For 10 years, my grandfather was forced to work in an isolated mountain area -where no human had been before in Vietnam- surrounded by police. After work, he listened to lectures on how great Hồ Chí Minh and communism were and how terrible capitalism was. He listened as the lecturers and films slandered South Vietnam, the slide he was a spy for, and pretended to show his love for Hồ Chí Minh to stay alive.

Later in the book, Bui recalls the time her parents were in Sài Gòn visiting family. It was January 30, 1968- the Tet Offensive. Since both sides had declared a ceasefire, many families that year had prepared large celebrations for Tết. That day, most members of the South Vietnam military were on leave. The police knocked on Bui’s grandparents’ door and requested to see everyone’s registration. Her father’s name was not on the list and he was forced to go home alone after confirming his identity, leaving his family behind.

On that same day in Huế, my grandparents had heard a cannon go off near their house. My grandfather climbed onto the roof of the house and saw members of Việt Cộng camped in the front yard. The smoky outside of the house juxtaposed the interior, which was covered in decorations to welcome the new year and had tables filled with bánh chưng and candied fruits. However, in a corner of the house was my grandfather’s military uniform and gun. He ended up jumping roofs until he reached his military base while my grandmother hid any materials relating to military involvement under the toilet. My grandmother’s actions saved my dad’s side of the family that day. In the evening, members of the Việt Cộng knocked on my grandmother’s door and asked for food. She gave them her candied ginger and the following day, they came back requesting more “coughing medicine.” Like Bui’s family, my family also spent the Tết of 1968 separated and scared.

The anecdote that stood out to me the most was when Bui’s father came into contact with General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan. Nguyễn is commonly known as the executioner in Eddie Adams’s Saigon Execution photograph – the image that depicted South Vietnam as unjust. However, Bui does not describe him as this historical villain. She writes about how Nguyễn hurt her father during a police check and told a subordinate to “give this hippie a haircut” instead.

It is retellings like Bui’s where readers are able to gain a new perspective regarding the people of Vietnam during the War. Reading these moments was refreshing, especially since civilian stories are often overlooked; it gave me a glimpse into what growing up and living through war looked like – that the effects do not go away just because the foreign troops and media did. This memoir truly humanizes the people of Vietnam more than American war films like Platoon, whose scenes involving Vietnamese citizens focused mainly on war crimes committed against them.

The Best We Could Do reinforces the adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” (“pictures” in this case). The rust-watercolor theme paired with the minimalistic illustrations creates a visceral reading experience. Her illustrations, though simple, were beautifully expressive and a vital part of Bui’s storytelling; each image feels like a whole story within itself. She captures the still faces of villagers, marked by grief and fear, as they wade through dark waters at night to escape French soldiers who are destroying their village. She captures the playful movements of children at her refugee camp in Pulau Besar as they swim in the ocean, enjoying a break from their former lives in Việt Nam.

While reading this book, I felt like Bui wrote it for herself and for her family, and for that reason, I feel somewhat guilty about rating this book. Guilt aside, I rate Bui’s memoir 5/5. As I arrived at the ending of The Best We Could Do, there was one phrase that kept on repeating in my head: “không bao giờ quên quê hương” (never forget your home). As the book progresses, Bui begins to see her parents in a new light and understand that they did the best they could do to provide her with a better life given their circumstances. Through learning about the history of her parents and grandparents, Bui, and readers, discover what it means to be a parent: endless sacrifices and unspoken love.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Carnegie Vanguard High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs and fund field trips, competition fees, and equipment. We appreciate your support!

Jessica Lin • Mar 8, 2022 at 2:09 pm

I hadn’t heard of this book, but it seems very interesting. Your review highlights a part of history that I’m not really informed about, but you explain it really well. I also really enjoyed hearing about your family story.

Noah Mohamed • Mar 8, 2022 at 2:04 pm

I really like the way you tie the stories within the book to your own family anecdotes using the excerpts from the book. Really interesting!