‘Our Missing Hearts’: a dystopian novel’s reminder of our society’s shortcomings

Our Missing Hearts is a dystopian novel that explores anti-Asian violence and discrimination.

Heart-rendingly descriptive, Celeste Ng’s Our Missing Hearts illustrates a dystopian society that is uncomfortably close to our own. The book is a deeply disturbing and cautionary tale warning readers of the dangers of chauvinism. Ng’s words and scenes may resonate especially with minority readers, who may identify with scenes in this book. Although not a traditional dystopian novel, Ng’s world is horrifying in its own way.

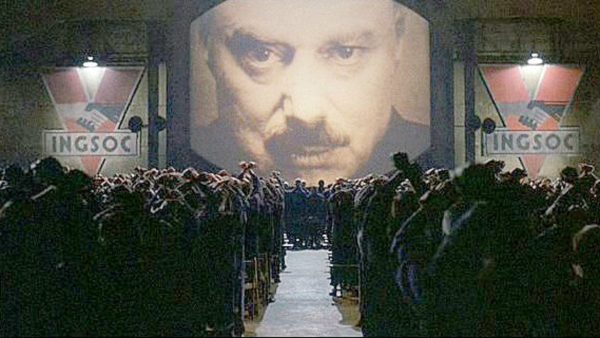

Ten years have passed since the Crisis, a period of economic and social instability in Ng’s fictional US. Violence and unemployment ravaged American society, leading to widespread fear and distrust. Unfairly or not, China was used as a scapegoat and blamed for America’s collapse. Americans began to turn on themselves, suspicious of those with features even remotely resembling Asian origins. The government’s response to this was to pass a law called PACT (Preserve American Culture and Traditions) which only served as an excuse for racist acts against minorities. Those who disagree with the law are scorned as un-American. “Seditious subversives. Traitorous Chinese sympathizers. Tumors on American society.”

Ng explores the thin line between nationalism and outright racism, particularly xenophobia, in a way that’s both timeless and timely. In Our Missing Hearts, government-sanctioned Anti-Asian sentiment is prominent, although disguised. PAOs (Persons of Asian Origin) were victims of harsh brutality by their fellow citizens.

In one jarring scene, an East Asian woman is forced to the ground and stomped on by a White man. After attacking her, the man turns on her dog, a tiny, white, harmless puff of fur. The look on his face is impassive as if he is just doing his duty as an American citizen. Even worse, none of the many onlookers rush to her aid, instead choosing to turn away.

Asian American hate is commonly marginalized and ignored, though horrific events are occasionally brought to light by the media. An example of such would be the 2021 Atlanta spa shootings, in which six out of the eight killed were of Asian descent, yet people refused to recognize the race-based correlation.

Less horrific, yet perhaps more relevant to the average person, Bird, the main character, faces bullying by his fellow students for his Asian-American features. They shun him, another trait of the real world.

In middle school, a boy called me a chink. He was white, and a year younger, angry about losing a game of Ultimate Frisbee, the epitome of middle school PE. His muttered curse probably hadn’t been directed towards me in particular – I hadn’t been contributing at all – but rather toward my team, which was composed of Asians. My school as a whole was primarily Asian, which would have made him the minority. I still don’t understand what he expected to accomplish – maybe he didn’t understand the significance of the term, which also could’ve been attributed to the reckless immaturity typical of 12-year-old boys. At the time, I laughed out of sheer bewilderment. Who was this kid? Even now, I look back and chuckle. I doubt he even remembers the event, a mere blip in his 7th-grade year. But I can’t forget. What remains with me was the casualness that accompanied the word, the ease with which it slipped past his lips, as if it was a mere common occurrence- one word amongst the millions of words over his lifetime. What made him say that? Why? Was it his upbringing? An external factor? Would he have sneered, told me to go back to my country, had I reacted?

Being a PAO, the authorities reminded everyone, was not itself a crime. PACT is not about race, the president was always saying, it is about patriotism and mindset.

Although plentiful with its political messages, Our Missing Hearts is, at its core, the story of a family torn apart by outside circumstances.

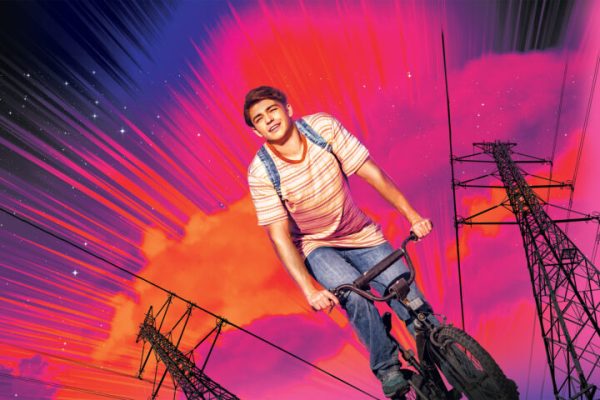

Bird Gardner is the main character of the story, which is told primarily from his first-person perspective. Twelve years old, he is just beginning to notice the injustices in his society, laws that don’t quite make sense. The tale takes place three years after the disappearance of his PAO mother, who left him to be raised by his White father.

His father is the librarian of a college library, one nearly empty of books. After the Crisis, books containing any ideas that might be considered traitorous are removed and pulped, calling the fellow dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451 to mind. Access to foreign ideas is completely removed, the cited reason being that they’re unpatriotic.

Control of media access is specially regulated with children.

When questioned about the lack of books on shelves, Bird’s science teacher reasons that books have become outdated and therefore, useless. In addition, she extolls their government for reducing the spread of unpatriotic ideas.

“Imagine a book that told you lies, the teacher went on. Or one that told you to do bad things, like hurt people, or hurt yourself. Your parents would never put a book like that on your bookshelf at home, would they?”

Honestly, at first thought, the teacher speaks reasonably. After all, there’s an extent to which content children should be allowed to view, for example, R-rated movies. However, Ng’s world takes it too far.

For example, the government seizes children from their homes if their parents expose them to “unpatriotic ideas.” In a society where the mere idea of freedom of speech is wildly contested, this so-called fictional world hits much too close to home. The media censorship in Our Missing Hearts aimed to remove “dangerous ideas” closely ties into America’s banning of books. For instance, 41% of banned novels contain LGBTQ+ characters, and 40% have minority characters in either primary or supporting roles. These novels are lambasted by religious and right-wing groups, who push for the removal of these books on the grounds of inappropriate content for children. Texas is the state with the most book bans, with Republican Texas Representative, Matt Krause, leading the way.

As a Texan who’s been a reader since childhood, both Krause’s words and Ng’s world terrify me.

I have fond memories of curling up and being satisfied to spend the day in my sunlit bed, with my only companion being a worn paper book, or perhaps two or three. Days where my only worry is not managing to finish books before dropping off to sleep. Days where I’m fully relaxed, with my head propped up by pillows, and half-lidded eyes barely skimming across the inky text.

These days, those perfect moments are being replaced with hours spent gazing at screens. Reading days are delegated to weekends if I’m lucky. Even though my book consumption rates have plummeted, those sunlit days are still a source of comfort and something I look forward to.

I almost can’t imagine a world where government control extends even to literature, to the mere spread of information. Many of the books on Krause’s list are littered amongst the primarily romance books that line my shelves, guilty pleasures. Ng forces us to consider a world in which the government is composed of only Matt Krauses.

Ng explores these metaphors throughout the book, drawing complex parallels between her fictional world and our reality. She takes ‘show, not tell’ to an extreme, delighting readers with graphic interpretations of mundane events. However, writing at times became monotonous, its evocative imagery failing to do its job and instead becoming repetitive and boring. Political references at times become over-wrought, but Ng’s masterful descriptions balance it out.

All in all, this book was interesting enough, though perhaps not necessarily thought-provoking- a solid 3.5 out of 5 stars. Our Missing Hearts doesn’t require much contemplation, due to the tendency to overelaborate most ideas, but it’s a fun read, perfect for when you’re in the oh-so-common mood to criticize the many flaws of American society.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Carnegie Vanguard High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs and fund field trips, competition fees, and equipment. We appreciate your support!

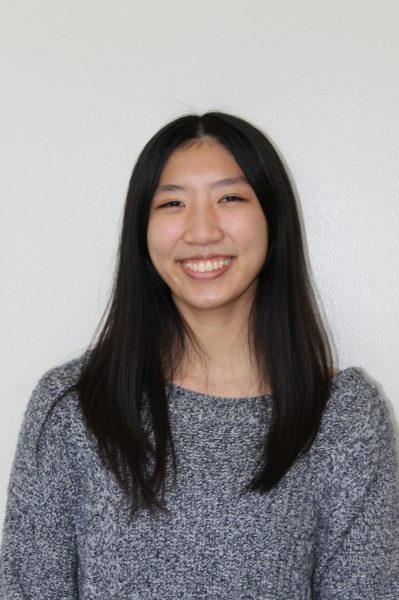

Natalia Nguyen is a junior at CVHS. She's incredibly dedicated to solitaire and Candy Crush Saga, two of her current favorite pastimes. She loves to read...

Bao Ngyuen • Nov 14, 2022 at 9:38 am

I <3 Celeste Ng's books, and I enjoyed reading your review on her newest novel (which I have yet to read)! There is a beautiful blend of your own experiences, timeliness, and it made the review extremely insightful and dimensional! Great job :,))