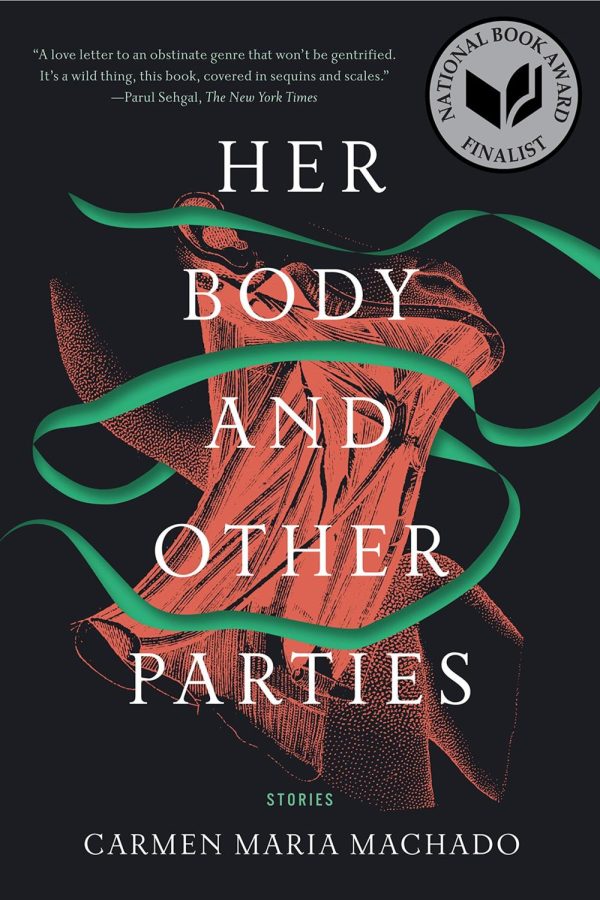

Her Body and Other Parties: cracking the code of queer womanhood

Her Body and Other Parties by Carmen Maria Machado weaves short stories on queer womanhood, from body dysmorphia to motherhood to sexual assault.

This story discusses sexual violence in a non-graphic manner.

Carmen Maria Machado’s anthology of short stories, Her Body and Other Parties, does its best to pull you in with intriguing plots, premises, and characters, and then sucker-punches you with the worst fact you never knew about yourself. Initially released in 2017, the book presents itself as a series of short stories, all unrelated apart from one common theme: womanhood. Even though each story within the anthology is meant to be read separately, reading them together seems to weave together its own plot, its own tale- one entirely separate from each individual premise. Each of Machado’s stories presents a different strife of womanhood but personified and given tangible form, all tackling a different issue and how many women face them, from body dysmorphia to motherhood to sexual assault.

Machado opens the novel with two quotes, one of which is by the poet Elizabeth Hewer. “god should have made girls lethal when he made monsters of men,” the quote reads, stylistically lowercase throughout. This perfectly sets the stage for the anthology, introducing the reader to a world where women are fully formed into what they feel they are, even if their true form may not reflect that. If a woman feels intensely about something, it is not simply pushed down, like it often is in real life- it takes real form. Each story within the book seems to shed light on the insecurities that many women have accepted simply as a part of life, brought forward not in an exaggerated manner, but in a manner that showcases how prevalent these issues truly are. Mundane aspects of womanhood are transformed into monsters, into real beings, into something concrete. Body dysmorphia and regret become a monster that lives within the floorboards, the sensationalization of sexual violence in the media takes form as a city that breathes, fear and insecurity and motherhood becomes a little green ribbon.

Within the anthology’s first story, The Husband Stitch, Machado weaves a tale of love and motherhood and shame and regret. Within it, a young woman infatuated with story-telling falls in love with a good man. She lives the perfect life with him; their sexual life is more than active, their child is intelligent (and male). There is only one catch- the woman has a small green ribbon around her neck which she refuses to take off. Fans of classic campfire horror stories likely know where that’s going, but I won’t spoil the ending for you. Regardless, throughout the story, the ribbon seems to act as a mark of the girl’s womanhood, representing everything from the worry a woman must feel for her child to the fear a woman must feel simply from being alive.

The story is also a little interactive- the author informs the reader at the beginning of the story that it is best read aloud to a group of people and gives instructions for those who choose to do so throughout. These instructions start reasonable but slowly decline into madness.

“If you are reading this story out loud, give a paring knife to the listeners and ask them to cut the tender flap of skin between your index finger and thumb,” the story informs after the woman has just given birth. “Afterward, thank them.”

The instructions definitely provide for a reading experience unlike any other.

While womanhood is the main trait that intertwines each story, one could argue that queerness is a trait that does so too. Machado does a wonderful job at including a queer woman in every single story of the anthology, whether that be in the form of the main character or in a main character’s daughter. A queer woman herself, Machado presents a variety of accurate queer representations, not including queer characters as only a token or a side note, as many authors often do, but as an essential to the story. If you were to remove a woman’s queer identity from her character, the story would simply not be the same- there is no sugar coating that. The motivations of half the characters, the reason characters exist the way they do, would simply cease to make sense if one tried to cleanse the queerness from Machado’s work.

The anthology’s fourth story is a work unlike any other, labeled Especially Heinous. A glorified fanfiction in the best way, the story tells its tale by rewriting the plot of each individual episode of SVU: Law and Order. Going title by title, Machado tells the reader of a world where ghosts of girls raped and murdered come back to haunt their detectives until their cases are solved, and the ghosts can finally receive peace. In Especially Heinous, New York City is living and breathing, and its food is the murdered. Its workers are doppelgangers and puppets. The city has become malicious, and it is up to everybody’s favorite special victim unit detectives, Benson and Stabler, to satisfy it and let it breathe.

“‘In the beginning, before the city, there was a creature. Genderless, ageless. The city flies on its back. We hear it, all of us, in one way or another. It demands sacrifices. But it can only eat what we give it’,” informs a character within the story to a woman trying her best to give peace to murdered ghost-girls with bell-eyes. Especially Heinous succeeds to do in 70 pages what L&O: SVU could never do in 23 seasons: give real humanity and justice to victims of sexual violence.

There is no woman (or person who had at one point identified as one) who will not find a story within the anthology that they see themselves in. A story that feels like it’s taking a magnifying glass to their own brain and pulling out words they’ve said, words they were going to say, words they’ve always wanted to say but never could. More than once, I had to put down the book just to think, “how did she know that about me?” It felt like Machado had reached her hand into my own mouth and ripped a receipt from my vocal cords purely to write simple dialogue. Perhaps I am biased, as a queer white woman who saw themself in most of the book’s main characters. Or maybe Machado really does crack some sort of code of queer womanhood within the pages of Her Body and Other Parties. I certainly think so.

One of the anthology’s final stories, Eight Bites, introduces you to a character who is both a mother and a daughter. The woman’s relationship with food is strained at best, weakened by her own mother’s disordered eating habits. Eight bites is all it took, her mother would always tell her before her death. One never needs to eat more than eight bites from any meal. Unable to follow their late mother’s unachievable standards, the woman’s sisters undergo a bariatric surgery in order to lose weight- one that permanently halves their stomach space. After seeing how happy it makes her sisters, how it finally allowed them to eat only eight bites, the woman decides to get it too. The woman’s own adult daughter, a woman named Cal who has long moved out, takes offense to this. The woman and her daughter have a falling out over their opinions on the surgery. After the woman gets the surgery, she receives another call from her daughter, where Cal reveals why she was so upset over it in the first place.

“‘Do you hate my body, Mom?’ she says. Her voice splinters in pain, as if she were about to cry. ‘You hated yours, clearly, but mine looks just like yours used to, so—’

‘Stop it.’

‘You think you’re going to be happy but this is not going to make you happy,’ she says.

‘I love you,’ I say.

‘Do you love every part of me?’”

The mother promptly hangs up and turns off her phone, welcoming a monster of shame and guilt into her house. Eight Bites perfectly encapsulates the heredity of body dysmorphia and eating issues, presenting both a realistic and fantastical look on one woman’s intertwined relationship with her family and her food.

Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties is the feminist’s modern classic. It masterfully weaves horror and romance and introspection together, all into less than three hundred pages. With a final rating of five out of five stars, I’d consider this book a must-read.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Carnegie Vanguard High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs and fund field trips, competition fees, and equipment. We appreciate your support!

Danielle is a senior, as well as an activist for queer and feminist rights, which often makes its way into her writing. She is a family and friendship-oriented...