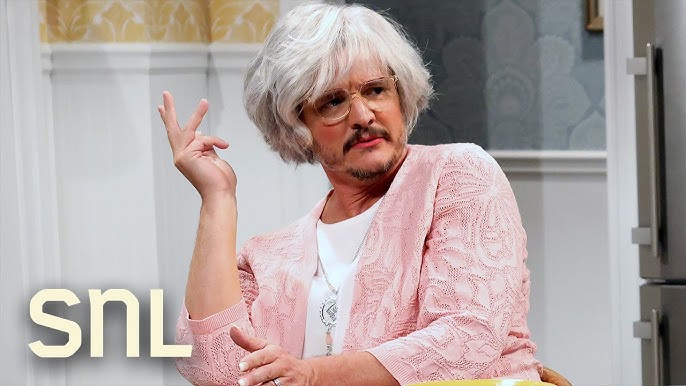

The clip of Pedro Pascal, the new dystopian hero turned heartthrob who captivated audiences as Joel in HBO’s “The Last of Us,” had already appeared on my Instagram feed several times just out of sheer popularity. Except, this time, he was dressed in a velour, pink tracksuit ensemble with lipstick and a gray wig.

A great actor is one who can perform as many different characters, and Pascal continued to prove he can play just about anyone. From a Satanist murder suspect in NYPD Blue, a protective and tough father figure, to your passive-aggressive Hispanic mom, Pascal can do it all.

I had seen these clips days after the initial October 21 broadcasting of SNL’s 2nd episode in their 49th season and did not watch the episode itself until days later with my tía. Bad Bunny served as the host of the episode and guest starred as the tía in this skit. I remembered bits and pieces of the first skit in this series, “Protective Mom 1.” In both these skits, Pedro Pascal plays a stereotypical Hispanic mom who is dissatisfied with her son’s (Marcello Hernández) white girlfriends.

I enjoyed “Protective Mom 2” more, because of the interactions between Bad Bunny and Pedro Pascal’s characters. Their lines played off each other’s comments. A prime example is when Bad Bunny tells Luis (Marcello) not to be angry with his mom for disliking his girlfriend, Chloe, but he takes it a bit further. He can stay with her, but not officially. “Ya no le importa si tu te metes con ella como un ‘booty call.’” Comedic genius drove this point home, with Luis’ own aunt encouraging him to keep Chloe as no more than a “side chick” or “sneaky link.” Hearing such slang terms accompanied by Spanish is in itself is funny, but the context of how his aunt, a woman, was telling Luis to treat another woman poorly only added to the irony.

The following scene, which was also the most widely circulated online, was the one that took the cake in my opinion. When Chloe, despite Luis’s efforts, tells his family of his depression diagnosis, Pascal delivers a firm and agitated, “Mi hijo does not have depression! He just likes the dark!” This hilarious quip elicited an uproar of laughter from the audience on TV and in my own living room.

Pascal continued to make the stomachs of many Latinos, and other people-of-color, hurt from laughter. “He tried to get it when he was a kid. He said, ‘Mommy, I’m depressed.’ I said don’t do that, do something else!” While the majority interpreted this as a highlight of ethnic communities disregarding mental health, I viewed it more in the context of my own Latino family. My abuelito, or grandfather, came to this country with nothing and eventually became a homeowner and citizen. In between those two stages was lots, and lots of hard work. I was taught early on that life will most certainly be hard, but it will also be beautiful. With the economic and discriminatory struggles some Latinos face, you had the right to be sad, but not for too long. They had to be productive to ensure the family’s fiscal well-being was maintained. They couldn’t dwell in their sadness, and they had to move on.

This idea is echoed in Pascal’s line. Several older and more traditional Latinos will relate to Pascal’s character, feeling that sadness, which is different from clinical depression, should not consume someone’s life, lest they develop the ability to farm their own food or produce their own electricity. In the Latino community and in general, I think there is a problem with the differentiation between sadness, an emotion everyone feels, and clinical depression, which can be debilitating. This can result in generational conflicts, such as those explored in this skit. Many other people of color, not just those of Latin descent, can draw similarities from the mother’s reaction to their own cultures, which solidified the skit’s relatability among non-Latino audiences.

In addition to the examination of generational conflicts, the skit has excellent use of language, alternating between Spanish and English, to ensure non-Spanish speaking audiences are still in the loop. Pascal’s mom exemplifies this in a one-liner that also reflects society’s view of interracial relationships and simultaneously establishes a social commentary.

When expressing her disapproval of Chloe and Luis’ relationship and possible children, the mom says, “Todo el mundo va tener que decir Tyler and Hayley Gonzalez.” Both the delivery and contents of this line are funny. It allows non-Spanish-speaking viewers to understand the point, while also pointing out how incongruous the names sound together, which brings me to my next point.

From the cookie tin Chloe gifted to her mother-in-law being turned into a sewing kit to the blonde highlights in Bad Bunny’s wig, the skit plays on stereotypes of Latinos. In this way, the differences between the cultures are brought up in a non-insulting way. Viewers on all sides found them funny, which shows the uniting aspect of comedy. Chloe had a septum piercing, which the mother then commented on by stating, “I have a piercing too, sept’ I’m putting it in my ear where it belongs.” This shows the conservative mindset of numerous older Latinos, without generalizing us Latinos as a whole.

Although the skit incorporated stereotypes, Latinos felt it connected to their lives. I certainly felt the same, especially when I saw the class Señora cardigan of Bad Bunny. While differences between groups are highlighted, both installments of the skit end in acceptance, showing the commonality and connection between people. At the end of “Protective Mom 2,” Pascal and Bad Bunny approve of Chloe once she gets mad at Luis for not eating enough. Pascal shouts “Give me Hayley! Give me Tyler!” before taking Chloe’s hand. Both the first and second installments of this skit end with the girlfriends’ welcoming to the family, showing that we all aren’t so different after all.

Katheryn Consuegra Pena • Dec 11, 2023 at 8:41 am

SO GOOD!! i loved that skit and what it means to hispanic families