SPOILER WARNING: This review contains spoilers for “The Boy and the Heron” !!

“A gray heron once told me that all gray herons are liars. So, is that the truth or a lie?”

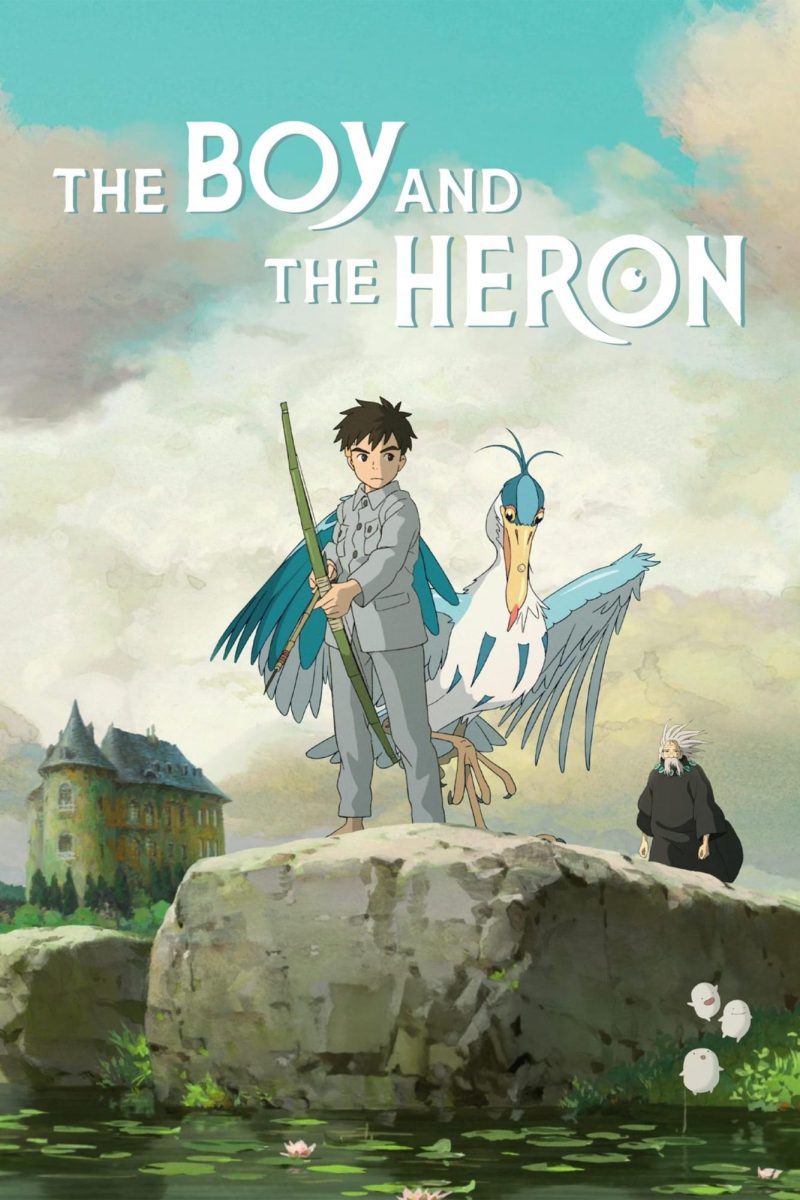

After a pivotal four decades of moviemaking, Studio Ghibli founder Hayao Miyazaki has finally announced his retirement from the world of animation, leaving us with one final film to conclude his career. In this heartfelt story of self-discovery and acceptance, a young boy navigates through a gray heron’s lies in hopes of accepting the truth.

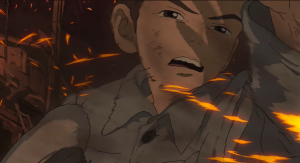

You’re probably already familiar with iconic Ghibli titles such as “My Neighbor Totoro,” “Ponyo,” and “Kiki’s Delivery Service”—movies loved and renowned for their whimsical and vibrant cuteness. However, contrasting this trope entirely, “The Boy and the Heron” opens with a scene of chaos and violence, in which a boy named Mahito (the protagonist) frantically pushes through hordes of people to reach a burning hospital where his bedridden mother resides.

I later learned that this particular scene was heavily inspired by Miyazaki’s own experiences from childhood. Being born in Japan during the Second World War, Miyazaki’s drew inspiration from his memories of “bombed-out cities” and other grueling visuals of war. Not only this, but Mahito’s deep emotional attachment to his late mother in the film mirrors Miyazaki’s love and respect for his own mother, who was similarly hospitalized for the majority of the filmmaker’s childhood. These autobiographical aspects added a nice personal touch to the already-unique opening scene; a subtle reflection of Miyazaki’s life and legacy.

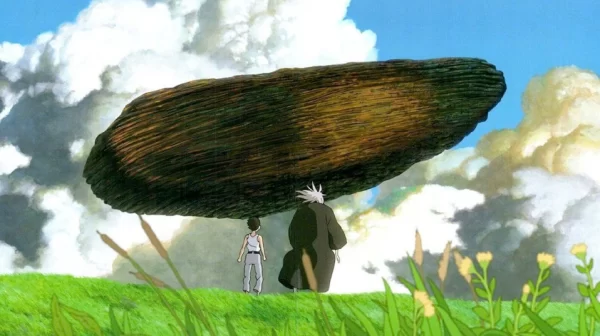

After the passing of his mother, Mahito moves to an isolated area where his new stepmother mysteriously disappears into a nearby forest. A talking gray heron (who has been pestering Mahito for weeks) then lures him toward a mysterious tower, claiming that his biological mother is still alive. Determined to believe this lie and find both of his moms, Mahito ventures in and is transported into a mystical realm.

This dreamlike world is very “classically Ghibli,” being filled with vivid color schemes, beautiful sceneries, and adorable imaginary creatures. However, despite retaining Ghibli’s signature cute charm, the darker and much more mature themes of this movie are brought out within this seemingly tranquil setting. An instance of this is the flight of the Warawara, tiny white creatures that represent unborn souls. Despite their outwardly innocent and adorable appearance, the Warawara reflect the destruction, violence, and ugliness of this imaginary world.

As the Warawara get ready to take flight and be born into the human realm, chaos erupts when pelicans, desperate to find food to survive, swoop down and devour them. Even amidst the frantic efforts to ward the birds off, many of the Warawara are set aflame and reduced to ashes. This scene had me shocked and taken aback that a Ghibli movie would illustrate the demise of their beloved characters.

The movie’s darker themes appear once again as Mahito and the heron invade a fortress guarded by sentient parakeets, hoping to rescue the boy’s captive stepmother. The parakeets—greedy, hungry, and plagued with selfish desire—attack and capture Mahito with the intention of eating him alive, once again showcasing the violence and corruption of this fantasy world.

Thankfully for Mahito, a mysterious fire-wielding girl comes to his rescue and frees him from the parakeets’ trap. Infiltrating the kingdom and singeing all enemies that stand in their way, the two eventually find Mahito’s stepmother and save her from the birds’ captivity.

At the end of the film, Mahito is asked to inherit his great-granduncle’s role of maintaining the balance of this magical realm with the opportunity to create a “perfect world.” Mahito ultimately refuses his great-granduncle’s proposal and chooses to return to his reality, rejecting the lie of perfection and with the new understanding that a real world is destined to have pain and loss.

This ending left me feeling deeply moved and in awe of Miyazaki’s masterful storytelling and character-writing skills. While other young boys in Ghibli films are typically portrayed as simple-minded and upbeat, Mahito turned out to be an extremely complex protagonist, grappling with trauma, vulnerabilities, and a profound fear of loss throughout the course of the movie. His uniquely pessimistic and impulsive personality also added a touch of realism and unpredictability to the film, leaving viewers to ponder the motives behind his actions. By completely diverging from older works and character tropes, Miyazaki was able to create a multifaceted character that takes effort to understand and love.

After returning to Japan with his stepmother and bidding farewell to his heron companion, Mahito gradually comes to terms with the death of his mother and is finally put at peace with his inner turmoils, content with the imperfections of the real world.

“The Boy and the Heron” was, to put it simply, a strikingly beautiful movie. Not only were the art, animation, and soundtrack absolutely gorgeous, but the story was exceptional, radiating the same ethereal and timeless charm of the classic Ghibli movies that we all know and love. This movie is an absolute must-watch for all art, film, and Studio Ghibli enthusiasts: a story that conveys the importance of embracing life’s inevitable endings, and serves as a fitting closure to Miyazaki’s legendary cinematic journey.

Kayla >:D • Jan 26, 2024 at 7:05 pm

Beautifully written! I LOVED this movie. It was such an amazing experience. Mahito is def one of my fav ghibli characters now too. He’s so real