Hurston, Morrison, Tretheway and more: Three quintessential female Black writers

Kara Walker’s commemoration ‘The New Yorker’ cover for Toni Morrison

Fifty-two years ago, in 1969, Black History Month was observed for the first time at Kent State University in Ohio. A short six years later, in 1976, President Gerald Ford nationally recognized the month-long celebration of the contributions of the people and events of the African diaspora. Today, Black History Month is annually observed nationally and internationally.

And while Black History Month, and Black culture in general, is increasingly recognized, in 2021 the state of Texas passed a bill that censors how public educators teach about the history of racism in America. The controversial bill, dubbed the ‘Critical Race Theory bill’, specifically bans the teaching of Critical Race Theory, an academic term for the study of how race and racism have affected the development of our nation’s social and political structures.

Despite this, or perhaps in spite of this, it is important to continue to educate ourselves and recognize the achievements of all underrepresented Americans, every day of the year.

So, this February I want to introduce a few works of literature by three of my favorite female Black authors. Happy Black History Month!

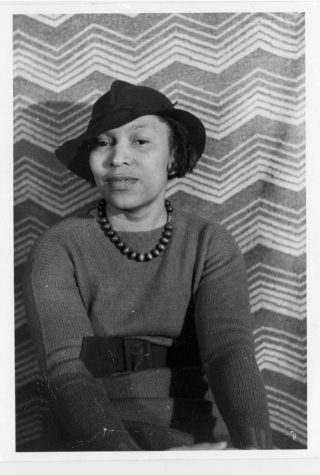

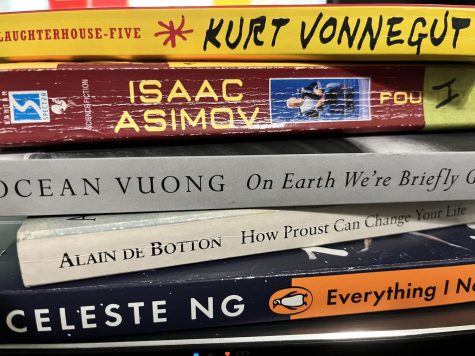

Their Eyes Were Watching God, Zora Neale Hurston, 1937

“Night was striding across nothingness with the whole round world in his hands . . . They sat in company with the others in other shanties, their eyes straining against cruel walls and their souls asking if He meant to measure their puny might against His. They seemed to be staring at the dark, but their eyes were watching God.”

Zora Neale Hurston, who was born the fifth of eight children in rural Alabama, was an anthropologist, writer, and contributor to the Harlem Renaissance and the Jazz Age at a time when very few women were recognized.

Their Eyes Were Watching God, one of her earlier novels and most recognized works, tells the story of Janie, a resilient Black woman who suffers two unhappy marriages and life in a deeply segregated South, among other struggles. With the semi-autobiographical Janie, Hurston brought to life a Black heroine at a time when there were largely none written. In her elegantly simplistic style Hurston takes us through the innovative and happy all-Black community of Eatonville, the real Florida town Hurston was raised in, and later the charming paradise that was the Everglades. More than all this, however, in Janie Hurston wrote into existence a heroine who did the unthinkable: dared to seek self-fulfillment and her own happiness decades before both the Civil Rights and Women’s Liberation movements.

Because of this, Hurston’s novel (despite being poorly received upon release) later became a staple of feminist and Black literature. And deservedly so, because perhaps for the first time a Black woman was not just written, but shown as a layered, strong, thoughtful, and mighty individual. While Hurston’s novel was indeed revolutionary for 1937 ( a story of Black love and independent female mindedness was far from the norm), the earnesty with which it was written, the thoughtfully simplistic prose is what enchants us still to this day. “She didn’t read books so she didn’t know that she was the world and the heavens boiled down to a drop.”

The book is also famous for its use of African American Vernacular in dialogue, it is one of the first and most famous examples of a Black author incorporating Southern dialect and expressions of Black people at the time in literature. This utilization of casual dialect lets the simplest of characters or phrases paint scenes colorfully,“Moon’s too pretty fuh anybody tuh be sleepin’ it away”

In short, Zora Neale Hurston conveyed her people, her message, her very own self, in the most powerful way possible; by doing it authentically. It is the resonation people felt when reading themselves on the pages that made her novel famous. And it is that same unpretentious genuinity that attracts us 80 years later.

Beloved, Toni Morrison, 1987

Haunting. If there is one word to describe Toni Morrison’s 1987 tour de force, it is ‘haunting’.

‘Beloved’ takes place mostly in Morrison’s home state of Ohio, in the year 1873, less than a decade after the end of the Civil War. And while the war may technically be over, and all former slaves emancipated, 124 Bluestone road, home to mother Sethe, and daughter, Denver, has yet to find peace.

Sethe was born into slavery on a southern plantation, then sold to work at ‘Sweet Home’, in Kentucky. There she is treated cruelly, as an animal rather than a woman, at the hands of Schoolteacher, the wickedly brutal slave owner. Sethe, heavily pregnant, and her three children eventually escape across the Ohio, but not before enduring the dehumanizing abuse of Schoolteacher.

“Clever, but Schoolteacher beat him anyways to show him definitions belonged to the definers– not the defined”

This is what Beloved does most famously: describe the horrors of slavery in not just simple words, but deep feeling prose that resonates, booms throughout the novel. Perhaps some of the novel’s intensity is drawn from the fact it is partially based in reality: Margaret Garner, like Sethe, was a real woman who fled to Ohio from Kentucky in the late 1850s. When she was apprehended by authorities acting under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Garner killed her two-year-old daughter, rather than see her return to slavery.

This complex understanding of freedom is yet another persistent theme throughout Beloved. A free Sethe chooses death for her and her children, over life as slaves. For this decision, she is ostracized, banished from Cincinnati’s freed Black community. The book challenges what we believe freedom to be, the everyday liberties we exercise, that were withheld only a century and a half ago.

Here Morrison, through Paul D, a former slave of Sweet Home, describes freedom and the danger of ‘loving big’ as a slave,

“Grassblades, salamanders, spiders, woodpeckers, beetles, a kingdom of ants. Anything bigger wouldn’t do. A woman, a child, a brother– a big love like that would split you wide open in Alfred, Georgia. He knew exactly what she meant: to get to a place where you could be anything you chose– not need permission for desire– well now, that was freedom.”

A final, and equally important though often understated, theme of Beloved is resilience, courage, and bravery. Bravery demonstrated by the freedmen of Cincinnati, who despite slavery and the war’s long, long shadow, built and nurtured community. The resilience of Sethe, who, absent of community and husband, single-handedly supports herself and her daughter Denver.

Beloved is an attempt to illustrate the early post-Civil War Black experience. The jarring brutality of slavery, the atrocity of the war, and the suddenness of emancipation, all of these come together. And despite the graphic, hard-to-read descriptions of Sethe and other former slaves’ worst humiliations, what Beloved is at its very core, is a testament to the immense resilience of Blackness. In my opinion, there is hardly a more powerful, nor important, book to be read.

‘“Sethe,” he says, “me and you, we got more yesterday than anybody. We

need some kind of tomorrow.”

He leans over and takes her hand. With the other he touches her face. “You

your best thing, Sethe. You are.” His holding fingers are holding hers.

“Me? Me?”’

Enlightenment, Natasha Tretheway, 2012

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/57697/enlightenment-56d23b7175cc0

Natasha Tretheway, a two-time United States poet laureate, Pulitzer prize winner, and current professor of English at Northwestern University, is an almost impossibly accomplished poet. Tretheway, who is the product of a mixed-race marriage, often explores the unique nuances of being a southern, mixed-race Black woman. This specific poem, Enlightenment, is from her anthology entitled ‘Thrall’. In Thrall, a word that means “the state of being in someone’s power or having great power over someone, ” Tretheway explores racial attitudes and the nuances of being raised by parents of two different races.

The poem begins with an observation of a portrait of Thomas Jefferson, our nation’s third president, who is perhaps most revered for his authoring the declaration of independence. And, as Tretheway notes, while he penned into existence our right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and declared that all men are born equal, he also owned over 600 slaves in his lifetime and infamously engaged in an extramarital affair with his mixed-race slave, Sally Hemmings.

In Enlightenment, Tretheway speaks of the ‘dark subtext’ that two-toned shading seems to add to Jefferson’s portrait, and refers to his owning of slaves as being a necessity, and his fathering illegitimate mixed-race children a ‘shortcoming’ despite his knowledge and ideals.

What Tretheway is doing is coming to terms with her heritage as America itself comes to terms with the imperfections of our founding and founders.

“ The first time I saw the painting, I listened

as my father explained the contradictions:

how Jefferson hated slavery, though — out

of necessity, my father said — had to own

slaves; that his moral philosophy meant

he could not have fathered those children:

would have been impossible, my father said.”

The short 18 verse poem addresses complex problems in a few words, but the

magic of Tretheway is that in the end, Enlightened is about something impossibly simple but

achingly nuanced: a father and his daughter.

Malcolm X once said, “The most neglected person in America is the Black woman.” This sentiment is what I feel makes each piece so essential: they uplift and underscore the nuances and resilience of an often misrepresented demographic. Beyond this, what is so enduring about each of these authors and their works is their ability to find the most achingly gorgeous words to describe the simplest of things. In all three works, each author attempts to find meaning and pride in who they are: their respective heritages and struggles. There is metaphor, rhyme, and beauty in every word; whether it’s’ the chapter in Their Eyes Were Watching God where Janie is beaten, or the line in Enlightenment where Tretheway states ‘Jefferson’s words made flesh in my flesh’, there is significance and meaning in it all.

Because of this, and more, I feel that all three are important, if not imperative authors and works to consider for Black History Month.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Carnegie Vanguard High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs and fund field trips, competition fees, and equipment. We appreciate your support!

Howdy! My name is Sofia Hegstrom and I am a senior who loves to read.

Jessica Lin • Feb 18, 2022 at 2:24 pm

I loved how much detail you put into your reviews. You provided great historical context, and all the books you picked have great cultural significance.

Noah Mohamed • Feb 18, 2022 at 2:05 pm

I really liked the way you used excerpts from the books/poem to give us a better idea of what they were actually like. It’s definitely a lot more engaging and helps us understand your dissection of the work without actually having read it ourselves.

Brooke Bushong • Feb 18, 2022 at 1:59 pm

this article is super informative and interesting to read