Ugly Feminism: ‘The Dropout’ Series Review

Spoilers for The Dropout ahead. Trigger warning for mention of sexual assault.

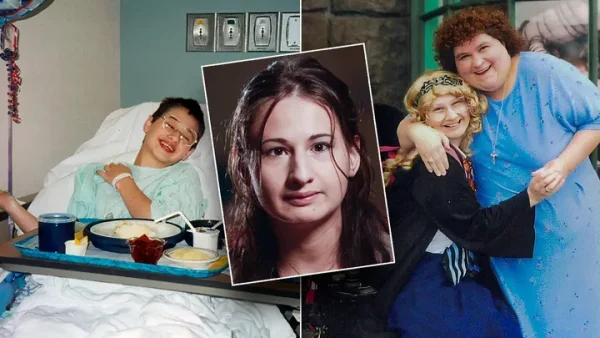

A woman, clothed head to toe in black. Black eyeliner widens the slightly terrifying stare she’s burning into you. Her lipstick is very, very red. Her face says, “I want it all.”

Her name is Elizabeth Holmes (Amanda Seyfried), and you are about to learn her entire life story over the course of eight episodes, titled The Dropout, and you won’t be able to look away for a second of it. At least, I wasn’t able to.

This Hulu hit limited series tells the surprisingly human corporate tale of Holmes’s abrupt rise and fall in Silicon Valley. Written by creator of New Girl Elizabeth Meriwether and directed by Michael Showalter, The Dropout takes on the ambitious feat of recanting the very real and very recent Theranos scandal.

Given the magnitude of the story the series was trying to portray, I was skeptical of just how much the series could cover and how accurate the series would be in a mere eight episodes. I would find out later that The Dropout nailed the true aspects of Holmes’s story basically over the head, but I would have been satisfied with the enthralling and amazingly produced story either way. If anything, Holmes’ simultaneous fast-track paths through her formative years and the corporate world seemed too absurd to be true at times. What was extremely believable, however, was the tale of Holmes’s plight as a woman in Silicon Valley. I had expected to see your run-of-the-mill misogyny in this series, but not the in-your-face, too-real, tragic undertones that Hulu delivered with The Dropout.

The series moves throughout Holmes’ life chronologically with cuts back to her 2017 deposition interspersed throughout the chronological storyline. Seyfried appears in front of a blue screen background, hair one step away from disheveled and blazer collar sticking up at questionable and unique angles every time we see her. Throughout the show, we see Elizabeth morph into the all black, Steve Jobs-esque look as if it were a second skin.

As the series documents Holmes’ life from early childhood, telling the story of an ambitious girl who would stop at nothing to be successful and was in a hurry to get there, I found myself rooting for her—to my dismay, I saw myself in her. She had goals from a young age, and big ones at that. Though hers were a lot more straightforward than my own vague ideas of success, I wanted to see her succeed so that I could know it was possible. I had heard of Elizabeth Holmes before watching The Dropout; I knew she would go on to deceive and endanger millions, but I still wanted that indulgent experience of seeing a woman make it big in a male-dominated industry.

And I did get those self-satisfactory moments of witnessing Elizabeth Holmes’s success, but each one came with a bitter aftertaste. Her first successful trial in front of investors was a fraud. She fired my favorite supporting characters, the scientists and engineers that created her miracle of a product, after they questioned the lab’s increasing secrecy. Everything leading up to and including the peak of her success—which some would say was her being named one of Forbes magazine’s 30 under 30—was built on a lie. She was a fraud.

And yet, we see her success perceived as the fruits of her genius by others throughout the series. (Before shit hits the fan for her, at least.) I seemed to learn about her growing reputation exclusively from other characters’ lines. Whether it was from her parents gushing about her success to others or headlines with her iconic portrait blown up beneath them, the audience receives news of her most recent successes through everyone but Holmes herself. To me, this was genius screenwriting—it emphasized Holmes’s facade and how she had everyone so well for so long.

Well, she had almost everyone fooled. The most telling part of The Dropout’s feminist message? Dr. Phyllis Gardner (Laurie Metcalf). The real-life and onscreen professor of medicine at Stanford informed Holmes several times of her ideas’ implausibility during Holmes’ short-lived time at the university. She’d be the first to denounce Holmes’s so-called “genius,” both in The Dropout and in reality. One of my favorite lines in the show is hers: “…How many chances are women going to get to do what she’s doing?…She screws this up, and we all look bad. That’s the ugly truth.”

But, as she seems to do in most other instances, Holmes persevered. Years later, she criticized Dr. Gardner’s discouragement of her ambitions. She called Gardner’s attitude towards her success “unfortunate”—it was supposed to be women supporting women, she said. Girls as a united front. Holmes shook her head and grimaced as if genuinely disappointed by the way her relationship with the professor had gone. The most chilling part is that if I hadn’t known any better, if I’d visited Stanford University to see Holmes speak about how she made Theranos and was changing the world, I would have believed her. I would have absolutely believed that Dr. Gardner was simply, unfortunately, not a feminist.

Though painful to watch, I thought it was amazing to see this level of nuance in the representation of women’s issues on screen. It’s true that sometimes women are met with the sad reality that is internalized misogyny within other women. But in Holmes’ story, the truth is that Dr. Gardner wanted Holmes to succeed, but (for good and somewhat obvious reason) didn’t want her to cut corners and build her success off lies more. But one of the first corners Holmes cut was Dr. Gardner’s advice—”You don’t get to skip any steps.”—and one of the many lies she used to keep up her facade threw Dr. Gardner under the bus.

The Dropout hit me with yet another crude facet of being a woman early on in the series. During her freshman year at Stanford, we see Holmes struggle to fit in with the social atmosphere at Stanford. Dead-set on her early success, she develops tunnel vision for her studies. After some incessant teasing from her roommates, she finally lets her hair down (literally) and steps out of her bubble into the throes of a college party. Slow motion shots of party lights and tilting hallways, and then suddenly—

“She said it was rape,” one of Holmes’s roommates whispered over Holmes’s static figure, crumpled into a fetal position in bed.

“Do you believe her?” Is the other roommate’s response. They shrug.

Holmes and her mother report it to administration, but it’s “his word against mine,” Holmes says, and such is the tragic case for many other women. Here is when I was reminded of the harrowing 97% statistic, but strangely filled with a sense of gratitude for not leaving this out of Holmes’ story. Though she may have been a fraud, she is still a woman.

Of course, being a woman doesn’t excuse her. It isn’t a “get out of jail free” card. Womanhood cannot and will not vindicate Elizabeth Holmes. But it is an important part of her story, and I’m glad The Dropout told it.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Carnegie Vanguard High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs and fund field trips, competition fees, and equipment. We appreciate your support!

Ava Lim is a senior at CVHS. She's a lover of all things neat and pretty, and has a variety of hobbies, ranging from calligraphy to crochet. They love...