Op-Ed: Instant photography is de-memorializing memory

Cat and Nat posing with stuffed animals, why? I wish I knew.

The air vibrates, humming through my bones. The crowd’s excitement is palpable, evidenced in the frenzied jumping that surrounds me, carrying me away, shrieks joining the deep bass thud of the music.

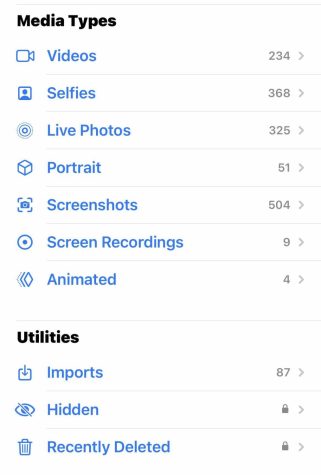

I tug my phone from my pocket, stepping away to get a clear shot, motions I’ve rehearsed a million times, once for every occasion. As I watch the scene through the black frame of my iPhone camera, I pause to check that the concentric Live Photo button is colored yellow, for on. I line up my thumb. Point, shoot, and snap.

Then continue snapping, until I’m confident in the ability of my phone to capture the moment in a way that I’ll be able to share with my friends later, in an Instagrammable moment that seems larger than reality, the reality that I’m currently viewing through the grainy lens of my iPhone.

Every so often, someone brings up the familiar question of “do you remember what happened on XYZ?” Usually, I give a vague generalization, but more times than not, my response would be something along the lines of: “Let me check.” There’s a sense of comfort knowing that my camera roll can make up for my forgetfulness, yet it feels as if I’ve lost something in return. The photos, whether or not they properly capture the moment, lack the same feelings I felt in the moment.

In moments like these, digital photography is a mixed blessing in its ability to both capture and lose important memories. According to Vox, scientists discovered constant photo taking diminishes our ability to recall our experiences, diverts our attention, and takes us out of the moment.

“As the prices of digital cameras went down and the quality went up, people realized they could take a lot more pictures with a lot less difficulty,” ASU Online said, “Even a mediocre camera or an iPhone can take pictures that in many ways rival the quality of professional film photography from 20 years ago. Once you’ve purchased a camera, you can take thousands of pictures without having to buy anything other than a reusable memory card.” Images are meant to store memories for one to relive in coming years, but the digital photography is taking away their ability to draw emotional significance. The problem that stems from the availability of picture taking tools isn’t the pictures themselves, rather the feelings, or lack thereof, elicited upon the rare reflection. By focusing on the action of taking pictures of events, people miss out on the events themselves.

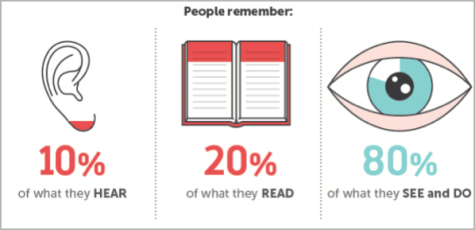

One running hypothesis is that when people stop to physically take a photograph, they temporarily disengage from the moment they are living to handle that quick task. As a result, this theory suggests, their brains encode the moment less deeply than they might otherwise.

In other words, taking pictures makes moments less meaningful.

One might argue that pictures are meant to preserve memories, simply serving as quick snapshots of moments in time, but the more photos that are taken, the less those memories matter. “When people take the time to study what they want to take pictures of and zoom in on specific elements they’re hoping to remember, memories become more deeply embedded in the subconscious,” said Alixandra Barasch, a business professor at New York University, in an NPR interview.

However, the sheer volume of digital photos detract from the significance of it all.

“When people rely on technology to remember something for them, they’re essentially outsourcing their memory,” said Linda Henkel, a psychology professor at Fairfield University. “They know their camera is capturing that moment for them, so they don’t pay full attention to it in a way that might help them remember.”

If I think back to that concert, the clearest memory I have is of my phone screen, literally. I’ve memorized the harsh yellow lines that streak vertically across the screen – byproducts of the many times I’ve dropped my phone – but they’re not that bad, I swear. I can recall the specific blurriness that occurs when zooming in to anything more than 1.0x – another byproduct, perhaps? I have no idea.

My phone functions as a filter, editing both my memories and photos, for better or worse. I’m starting to view the world through my hazy, broken, camera lens. What should be fond recollections are immortalized by blurry photos (I look better in them, and they’re not exactly hard to take), piling up in my lonely Photos app, never to be rediscovered.

As a person who heavily relies on images to recall certain moments, there will always be a form of reliance towards my phone, but even I can acknowledge moments without them are more meaningful. After iFest this year, my friends and I went out for dinner to enjoy the night before its end. We had established a “no phones at the dinner table” rule as a joke, but it seems to have brought us more beneficial effects than we originally believed. Having already taken plenty of photos during the event, any time left was meant for those bonding discussions meant for our ears only. That night, although I don’t have the clearest recollection of it, still lives as one of the most unforgettable moments within that friend group. We didn’t need cameras to remember how much fun we had, but we had taken enough photos so we could reflect when our memory turned hazy.

To combat the battle between camera and experience, people can focus on taking a few good photos highlighting an important detail or moment, then placing the camera away. Our brains create long lasting memories by linking sensation neurons which allow us to remember the scene, the scent, everything. The stronger the neurological connection, the stronger the memory will be. If we don’t pay attention, however, we’re not gaining the same experience that allows our brain to develop strong recollection of events.

Thus, next time you’re hanging out with family and friends, try to think less about pictures and more about enjoying the moment and the environment around you.

By limiting the time with a camera out, you’ll have more time to live, laugh, love.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Carnegie Vanguard High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs and fund field trips, competition fees, and equipment. We appreciate your support!

Cat is a sophomore on the Carnegie competitive dance team and enjoys reading, more specifically fantasy genres, and writing in their free time. They also...

Natalia Nguyen is a junior at CVHS. She's incredibly dedicated to solitaire and Candy Crush Saga, two of her current favorite pastimes. She loves to read...

Sasha • Dec 13, 2022 at 12:14 pm

This article is so well-written! It made me reflect on how I recorded so much at concerts, and should be more present.

Bao Ngyuen • Dec 13, 2022 at 10:21 am

The pikachu plush drew me into the article, and I’m glad I stayed!! I love the message of this article, especially in a technology-reliant world