Race and Coronavirus in America

Being Black in America might make you more susceptible to COVID-19

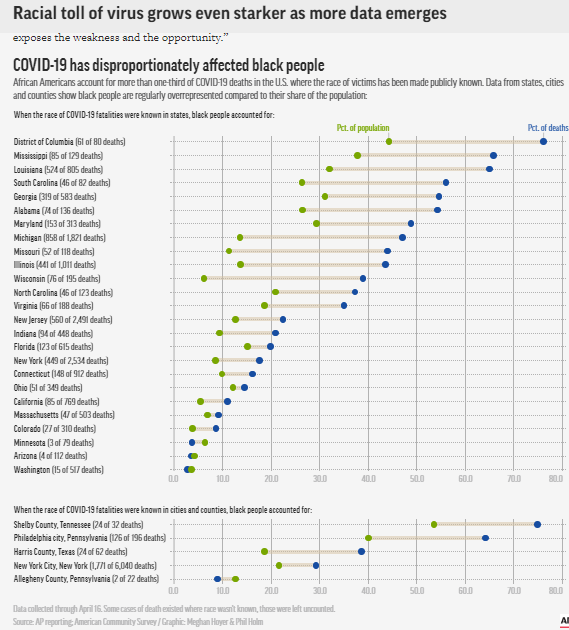

The virus that “doesn’t discriminate” has disproportionately affected black communities.

COVID-19 and it’s rising death toll have become matters of concern for every person on Earth, after achieving pandemic status. Unfortunately, in America, the concern is greater for some groups of people than others. Recently, networks like CNN have been casting segments of slideshows, displaying some of those that have passed from complications related to the virus. Their names and bios are read while somber music plays in the background. Among these photos, one can not help but notice a pattern: most of these people displayed are Black.

In America, African Americans account for 52% of nationwide diagnoses, and 58% of nationwide deaths, according to the most recent studies. It is also important to consider that this same group of people make up less than 13% of the country’s population. These numbers are almost comparable with this country’s prison rates, but that’s for another article. There is a clear racial gap concerning the susceptibility to the virus’s fatal grasp. Questions begin to form: Are Black people just, inherently, more virus prone? Is there a deeper issue at hand?

One major cause for this race gap in virus affliction is food insecurity. Many Black neighborhoods in America are considered food deserts. For those that are not familiar, food deserts are areas and neighborhoods with limited or no access to healthy, nutritional options. Because of their location in relation to farms, or a low median income in their area, many families are left without healthy options at local grocery stores. This includes organic–or fresh at the least–fruits and vegetables. This is a prevalent issue in the community, and, according to a BBC study, “Black US households in 2018 were twice as likely to be food insecure as the national average, with one in five families lacking consistent access to enough food.” While it is estimated that “23.5 million people live in food deserts,” according to DoSomething.org, the number might actually be greater. The same source notes how “[T]he North American Industry Classification System places small corner grocery stores (which often primarily sell packaged food) in the same category as grocery stores like Safeway and Whole Foods.” This denies the public accurate data on who actually has access to healthy food: suppressing the issue, oppressing the hungry.

If these options are available, poverty makes them solely ornamental. Half of the families in food deserts cannot afford the healthier options, resorting to cheaper alternatives, which are almost always more nutritionally harmful. When people’s diets are based on cheap, saturated fat-riddled, fast food, it can lead to harmful conditions like heart and lung disease. One thing that most have learned from health warnings during this time: COVID-19 targets those with preexisting conditions. If some Black Americans are more likely to be deficient of basic nutrition, how can they possibly stand to fight a pandemic that preys on that specific situation?

A virus that has no eyes or ears–certainly no ability to comprehend the oppressive, racially driven, American mentality–seems to be targeting African Americans at a disproportionate rate. This affects not only those that pass away and their families, but all African Americans in this country, who are, first and foremost, Americans. This is a problem that is affecting and killing Americans. While the pandemic has shown itself as a racial issue, this is not only a Black problem. This is a problem for all Americans to consider and work to combat.

The solutions to an unequal rate is clear: work for better nutrition in these neighborhoods; create legislation that might establish sufficient sources for healthy food options in impoverished neighborhoods; integrate nutritional health education into local curriculums, so young students can learn how to build healthy diets; establishing initiatives from supermarkets to open locations in food insecure areas. Unfortunately, all of these solutions seem like too much effort for those that have the power to execute them.

Although a lot of blame can be placed on systemic racism and the predisposition to poverty that many Black people struggle against everyday, it is important to take matters into our own hands. Because of these alarming statistics, all Americans should take heed of the stay at home suggestions. African Americans, especially, should take these suggestions seriously and with great gravity. Quarantine is the most effective way of fighting this pandemic, besides an actual vaccination (which, in itself, can be problematic, depending on your inclination to conspiracy theories). It is the job of everyday civilians to do our best to reprieve those that are on the front line, such as nurses and doctors.

There are many ways to go about combating this issue, but the first and most important task that needs to be completed is acknowledging the issue, and understanding its consequences, which are currently life and death. The conversation is what opens the doors to reform. As Americans, we have to recognize and call attention to the wrong we see everyday. As community members, we need to act. If our local, state or national governments aren’t going to stand up for this group of people, we must stand up ourselves.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Carnegie Vanguard High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs and fund field trips, competition fees, and equipment. We appreciate your support!

Hey y'all! I'm Ash, and I'm a staff writer for Upstream News. It's a great way for me to stay updated and connected with the school and the world. ...

Lexy Silva • Jan 21, 2021 at 10:33 am

so well written, organization, structure and language and choice of outside evidence really helps you get your opinion across

Angel Zepeda • May 14, 2020 at 5:10 am

While it is understandable that this is an opinion piece, many arguments stated in the article are simply not investigated with enough depth to make a concise argument. When first beginning to speak of the “nationwide” diagnosis demographics, some percentages are given. Even though in the above stated demographic where only 25 states are demonstrated and sources such as the Atlantic which address that only about 29 states have actually released racial demographics for the infected. Leading to the question of how the percentages of said “nationwide patterns” are actually calculated if about how the United States remains unaccounted for, which ends up ruining the credibility of the article, and sources which are not mentioned anywhere other than the demographic. Later Ashton, quickly passes over the fact that what I can only assume he is referring to is the 52% and 58% he mentions prior to being around the country prison rate for African Americans. Which is simply nonfactual as the US Bureau of Justice states that Black males make up 33% of american prison population, while white males are only at 30%. While the inverse is said for females, as white women make up for more than 49% of the prison population. Yet more than half of all murder cases recorded by police are done by African Americans, which only compose an estimated 13% of the nationwide population. Moving on, Ashton states that one of the causes for this race gap from the virus is because of food insecurity and, because many Black neighborhoods have low median incomes. He first claims that 23.5 million people live in food deserts, but this statistic is not strictly African Americans but all races combined which end up making less than 3% of the nation’s population. Later he argues that low incomes lead to African American families buying cheap junk food loaded with saturated fats and processed ingredients because of how cheap it is compared to the otherwise healthier options. But in a study conducted by the US Department of Agriculture, it is actually cheaper to buy and live off of healthier more natural foods, rather than buying fast food or often frozen/canned meals. Based on overall pricing, and sheer abundance of the amount of produce or other such healthy alternatives you can get at just a fraction of the cost of your $30 McDonalds meal made up of Big Macs and McNuggets. Furthermore, a line in the article that strikes me is “A virus that has no eyes or ears–certainly no ability to comprehend the oppressive, racially driven, American mentality–seems to be targeting African Americans at a disproportionate rate.” In the aforementioned statement, I believe that the writer is referring to racism, or systemic racism. Which is simply not true, as now in the 21st Century in America, no laws are placed to specifically oppress certain people because of race. As it is, many high political powers are racially diverse while college, high school, and public settings are not segregated whatsoever. Moreover, when he begins to speak about vaccinations and states “ which in itself can be problematic” is something that should not have been written and has no basis for said claims. As no factual, medical, or scientific articles have ever been written to claim that vaccinations are bad or pose any threat to the human body other than the immune system’s initial encounter with the virus itself. This statement simply spreads a false narrative and nonfactual propaganda, that plagues everyday media and has influenced a movement of Anti-Vaccinations that have made the American Society more dangerous thanks to the more people not contributing to the notion of herd immunity, which in itself has a scientific basis. In the concluding paragraph of the Opinion Piece Ashton sets forth a Call to Action. Simply by stating that if our governments are not going to stand up for the aforementioned group of people we must. This statement is confusing in and of itself, as the federal government has offered stimulus checks to all US citizens affected by the pandemic, and many school systems have held Food Donation sites one such district is our very own HISD. But if we truly want to see how we can make an everlasting change in the aforementioned neighborhoods, the change lies within those community members to change how it is they live their daily lives. As they have become habitually accustomed to buying cheap junk ready to eat food. While they should be reflecting on how they can and should create a health benefit for their families and themselves in the coming future and the present itself. Finally, this article fails at accurately demonstrating how “Being Black in America might make you more susceptible to COVID-19” which is a fabricated notion, in a culture of victimization that is present among the new generations of Americans that haven’t a clue about self-reflection and understanding the problems that they themselves cause to just expect the government or others to come to their aid.

Dave Muzyka • May 13, 2020 at 1:13 pm

Nice job Ashton! Beautifully written!

Donald Lam • May 13, 2020 at 1:07 pm

Great piece of writing Ashton. I am so proud of you.

Mr. Lam

Melanie Porterie • May 13, 2020 at 1:01 pm

Great Article Ashton!!