Op-Ed: HISD needs to return to remote learning before its “return to normal”

Harris County issues a red COVID alert while HISD resumes school as usual.

Imagine breathing through a narrow straw. For a second. For five seconds. For five minutes. Five hours. Five days. A tight band is wrapped around your chest and every breath brings a new wave of fire into your lungs. But you have to fight to breathe. Again. And again.

That is the reality of more than a hundred thousand people hospitalized with COVID-19 right now.

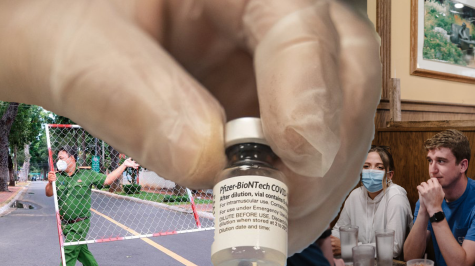

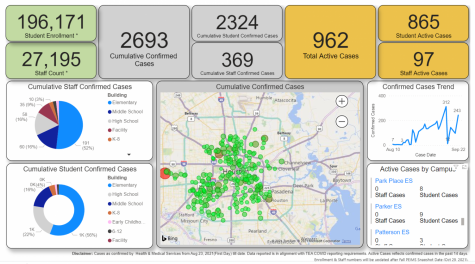

Rates of Omicron and other variants of COVID-19 are spiking throughout Houston. According to the Houston Chronicle, about a fourth of HISD students didn’t attend the first day back from winter break; the decision to continue school in-person without significant changes to protect students has shifted from controversial to near-criminally negligent.

By continuing in-person learning even in the wake of the largest wave of coronavirus infections in history, school districts have proven that the lives of the students they serve are worth less than the money.

Since the return to school, the decision to keep schools open even as cases increased was justified by the relatively low risk that children experienced compared to adults (questions about the health and safety of teachers were brushed off). Omicron, however, brings the faults in this reasoning to light. Because of the way that Omicron attacks the upper respiratory pathway, young children with small airways are especially vulnerable to swelling.

Compounded with the fact that most young children are unvaccinated (the FDA has only approved the vaccine for children 5 and above, and boosters are not approved for children under 12), it becomes clear that returning elementary students to remote learning is the only responsible choice for school districts to protect the children in their care.

“Rapid community spread is seeing larger numbers of children being hospitalized—again, mostly among the unvaccinated,” said Anthony Fauci, who has been a medical advisor to every president since Ronald Reagan.

Yet even in the face of these dangers, not only is HISD declining to return any schools to virtual learning, they are also closing the virtual academy offered to students that were either too young to be vaccinated or those who met the medical criteria.

“Once vaccines were available and approved, we wanted to encourage families to take advantage of those vaccines,” said HISD Chief Academic Officer Dr. Shawn Bird in a statement. “So, we are going to be closing down the virtual academy.”

The temporary learning academy for students who have tested positive for COVID will still be available.

The reasoning provided for this irresponsible move by HISD doesn’t seem to make sense. If anything, HISD should encourage students to get the vaccine before they return to school in-person. And even with the vaccine, students spend the entire day in close quarters with each other, further increasing the possibility of infection. By taking away one of the few safeguards students and their families have against coronavirus—remote learning—HISD is only putting its students and staff in more danger.

The answer to the latest wave of infections is simple on the surface: schools should return to the virtual learning that was a hallmark of the original pandemic solution.

CVHS English teacher Erica Harris misses the “peace of mind” of virtual learning. With in-person learning, she said, “There’s just a low hum–a constant hum of worry.”

CVHS senior Perrin Calzada expressed similar sentiments, adding that even vaccinated and boosted, he does “not feel as safe as I should. I see people with masks below their nose. I see people coming in from the outside with their mask off. I see people touching things after they touch themselves and that just being spread everywhere–that the prevalence of things being wiped down is very low,” said Calzada.

Due to the rising COVID level, schools and offices were closed on January 18th, which was originally intended to be a teacher in-service day. Faculty, staff, and students were encouraged to use the extra day to get tested before a return to school.

No other closures are anticipated, according to the HISD website.

The January 18th closure was a surprise, with the announcement coming after school hours on the 14th before the long weekend. And just like with that unexpected call, no one is quite sure who or what is barring HISD from going online now.

No one interviewed knew who makes the call on whether or not HISD returns to virtual learning. Possible answers ranged from the superintendent to the school board to the Texas Education Agency (TEA) to the Texas governor.

“I know it’s not the campus level,” said Harris. “Definitely not the teachers. Definitely not the people in the classroom.”

Clearly, students and staff alike don’t have a say in HISD’s decisions that directly impact their safety. If the district felt that the rising COVID level was dangerous enough warrant a day off, why do rising levels not warrant more time off—even a more realistic period of time for students and staff to get tested, and even quarantine if needed?

In the Chicago Public Schools, the Chicago Teachers Union took matters regarding COVID restrictions and transparency into their own hands. Unhappy with guidelines that they felt put themselves and their students at risk, the Union staged a five-day strike.

The final deal requires schools to close “if 30 percent or more of its teachers are absent for two consecutive days because of positive cases or quarantines, and if substitutes can’t get the absences under 25 percent,” according to a report by the Sun Times. Schools must also close if 40% or more of their students are quarantining.

“It’s sad we have to even take that kind of action for just the basics,” said Harris regarding the situation in Chicago. “I am in support of [them], ‘cause [teachers are] the ones that see y’all everyday.”

Besides the lack of transparency on the chain of command in HISD, there are endless other complications embroiled in the idea of returning to virtual learning.

“People are very tired,” said Calzada. “Everyone. They’re tired of having their kids at home. They’re tired of having to watch over them whenever we’re having classes and so they just want to send us off to the school to leave us here. Whether or not it’s safe is kind of irrelevant.”

Regardless of their usual policy of one-size-fits-all decisions, HISD could choose to organize their grade levels separately. Both Calzada and Harris pointed out that a separate solution might be required for elementary school students than could be feasible for middle schoolers and high schoolers, who require less at-home supervision.

“I think there should be the option to [return to remote learning],” said Harris. “Carnegie had a lot of students who were able to go virtual, you know, and some campuses can’t do that, but if you let campuses set up how they want to navigate the spring and maybe even the next year, that would also be really nice, because we know what’s best for y’all. And elementary schools are going to run differently than high schools and I just don’t know if that kind of nuance will be addressed.”

HISD is unlikely to give campuses that freedom. The refusal to lockdown is more deeply entrenched than a solely district problem.

As the largest school district in Texas, HISD has been plagued by funding issues for at least a decade. Moving against the wishes of state officials, like Texas Governor Greg Abbott who has been strongly against stricter restrictions since the beginning of the school year could put their annual per-student funding at risk.

Last year, TEA issued a waiver to allow schools who were entirely virtual to continue to receive funding as long as they met certain requirements, such as an in-person option. This year, they have neglected to renew that waiver, leaving open the possibility that schools who are not in-person might not receive funding.

“I think as a system…we need to really re-evaluate our expectations,” said Harris.

A total revision of priorities is possibly the only solution to a systemic problem that even a pandemic has been unable to solve. Sadly, an upheaval like that takes time–time students in Omicron-infected schools might not have.

In lieu of a complete shutdown, teachers and students agree that the least the district could do is provide more extensive safety measures while in-person.

“At least give the option of the N95 masks or the KN95 masks. The ones that we’re offered at school are helpful, but they are not proven to be as effective as those are and since we’re dealing with a version of the virus that is very contagious, I would like that,” said Calzada.

A properly worn N95, KN95, or KF94 mask can filter out between 95 and 94% of particles, said recent government updates on the effectiveness of various kinds of personal protective equipment (PPE). The medical masks provided by the district do not fit as tightly, greatly reducing their effectiveness.

Unfortunately, new safety measures from the district do not seem to be likely.

“I made a request through Mr. Moss to see if the district would be willing to [provide N95 or KN95 masks] for us or if there was any plans, and there isn’t,” said Harris.

Calzada has harsh words for whoever is neglecting district health priorities, whether that be by refusing to return to lockdown or by providing subpar PPE.

“A student’s health and safety should be our number one priority over even the quality of the education that they’re receiving at the time, over any sort of profit, over any sort of ‘return to normal’,” said Calzada, “because a dead child isn’t going to learn anything.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Carnegie Vanguard High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs and fund field trips, competition fees, and equipment. We appreciate your support!

Ava Lim is a senior at CVHS. She's a lover of all things neat and pretty, and has a variety of hobbies, ranging from calligraphy to crochet. They love...

Hi! My name is Brooke J Ferrell. I'm a senior who, if not writing, is usually rock climbing :)

Zainab Zaman • Feb 1, 2022 at 2:26 pm

I really love the imagery in the beginning that forces the reader to be put in that situation. The hyperlinks are also so helpful for understanding all aspects of the issue. LOVE Perrin’s final quote!

Julian Namerow • Feb 1, 2022 at 2:25 pm

THIS IS AMAZING OMG!!!!! love the start love the quote about the hum loved everything

Roxell • Feb 1, 2022 at 2:14 pm

What an eye opening story. That last quote really hit home. Good job guys!

Ankitha Lavi • Feb 1, 2022 at 2:11 pm

The ending quote is so good!!! I really like Ms. Harris’ idea of the schools giving K95 masks to students. It’s nice to see you calling out our district for not giving schools the proper resources to function without worry.